YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

Roshi Bernie Glassman never did anything by half. An aeronautical engineer turned pioneering American Zen teacher, he threw himself into mastering Zen’s many sutras, liturgies, and customs. Then, unsentimentally, he abandoned everything in Zen he felt didn’t fit him or the Western mind and broke open our ideas about Buddhism, showing us that it isn’t separate from social engagement.

Of course, Glassman threw himself headlong into that too, as he found innovative ways to feed the hungry, care for the sick, and bear witness to the world’s pain. He was the founder of the Zen Peacemakers and the Greyston Foundation, and it was his brainchild to take retreats out of the zendo and right into the pain of the world—into the streets with the homeless and to the sites of genocide in Auschwitz, Rwanda, and Wounded Knee.

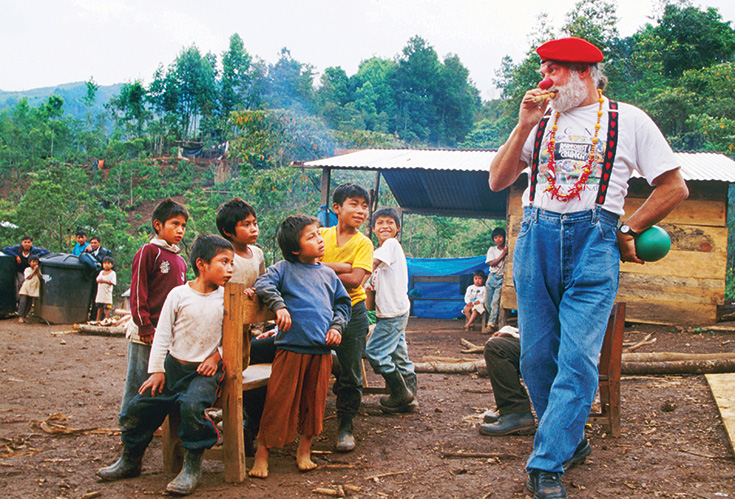

But Glassman was also a clown—literally—and he was always keen to don his clown nose, even while giving a dharma talk or talking politics. After all, something simple and silly like a red nose can change the whole tone of a room. Fierce and funny and freewheeling. Kindhearted and whip smart. That was Roshi Bernie Glassman, a man who was larger than life.

Early in the morning on November fourth, Glassman, aged seventy-nine, died of sepsis. His body was brought home, washed with water scented with herbs, and dressed in a Hawaiian shirt, jeans, and suspenders. They were his favorite clothes, which he’d been unable to wear since he’d suffered a stroke in 2016. Someone put a clown nose into one of his cupped hands, while his widow, Eve Marko, placed his wedding ring in the other.

Glassman’s mourners were many—Buddhist and non-Buddhist, in America and abroad. “He was the primary force of dharma and social action in this country,” says Frank Ostaseski, the guiding teacher of Zen Hospice Project in San Francisco. “The beautiful thing about Bernie was that he allowed everything. He allowed all voices to be heard, and that was wonderful to be around.”

“He was always willing to go to that place where we don’t know, which is the place of absolute creativity,” says Roshi Pat Enkyo O’Hara, abbot of the Village Zendo in New York City. Glassman, she asserts, “revolutionized Western Zen. He reminded us that ordinary mind means caring for every aspect of creation.”

Hozan Alan Senauke, former executive director of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, concludes, “Our debt to Bernie and the reach of his tender humanity cannot be fully seen.”

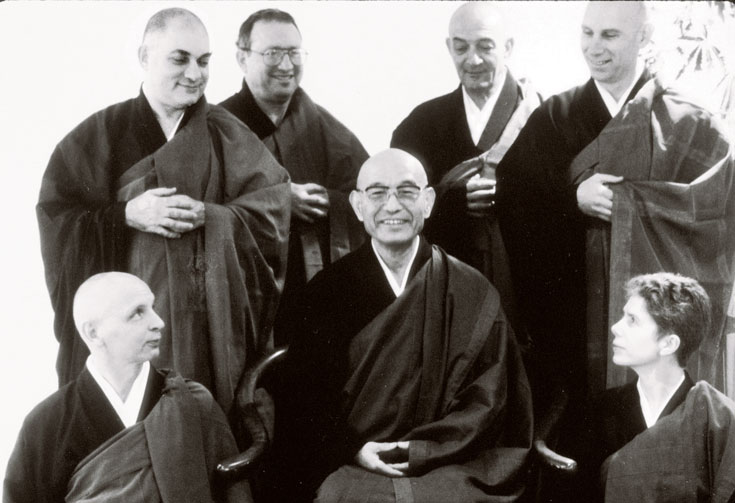

Taizan Maezumi Roshi (center) was a pivotal figure in the transmission of Zen Buddhism to the West. Bernie Glassman (top, left) was one of his twelve dharma successors.

Bernard Alan Glassman—known as Benyamin in Hebrew—was born in Brooklyn in 1939 to Eastern European immigrants with strong socialist leanings. His father was a printer and construction foreman. His mother, who’d lost many of her relatives in the Holocaust, worked in a factory. She died of mercury poisoning when Glassman was just a small boy, so he was raised by his four older sisters.

Glassman studied engineering at Brooklyn Polytechnic Institute, then he got an assistant teaching fellowship at the Technion-Israel Institute of Technology in Haifa. On the boat to Israel, he met his first wife, Helen Silverberg. The couple eventually moved to the West Coast, where Glassman got his PhD in applied mathematics at UCLA. He worked as an aeronautical engineer developing plans for NASA for what were expected to be manned spaceflights to Mars.

Glassman’s first taste of Zen came in 1958 when he read The Religions of Man by Huston Smith. While engineering and Zen may seem worlds apart to us, for Glassman there was no difference between them. Zen is all of life, he said, and in everything we do, we can bring to bear “the Zen of action, of living freely in the world without causing harm, of relieving our own suffering and the suffering of others.”

At first, Glassman tried practicing on his own, then he sought out teachers. It was in 1963 that he first met Taizan Maezumi Roshi, a legendary Zen master who played an instrumental role in establishing Zen in the West. At the time, Maezumi was just a young monk assisting an old roshi at a temple in Little Tokyo, Los Angeles. Glassman asked the old roshi why they punctuated their sitting practice with walking meditation. The roshi’s English was poor, so he indicated that Maezumi should respond. “When we walk, we just walk,” was all Maezumi said, and for Glassman this stripped-down response hit the mark.

Four years went by before Glassman happened to see Maezumi Roshi again. This time Glassman asked if he was part of any temple in town, and Maezumi said that he was just starting one. The very next day Glassman showed up at the nascent Zen Center of Los Angeles, and eventually, he, his wife, and their two children moved in. However, the young family continued to keep the Sabbath and the kids attended Jewish schools. As Roshi Joan Halifax, one of Glassman’s dharma heirs, has quipped, “Bernie was 100 percent Jewish and the rest was Buddhist.” Apparently “the rest” added up to a lot, as he became Maezumi Roshi’s right-hand man.

Maezumi, as Glassman remembered him, was a very soft person in a way, yet also very dogmatic. “In our private studies, he’d always tell me that he was Japanese and could not make an American Zen,” Glassman recalled. “But he could help me grasp the essence of Zen and I should swallow it all up and then spit out what didn’t work for me. In fact, when I was ready to go start my own center, he said, ‘I’ll stay away for a year because I don’t want to influence you.’”

Maezumi’s desire for Glassman to forge his own way stood in contrast to his rigid emphasis on linear hierarchy. The teacher–student relationship is clearly defined in traditional Japanese culture. As Glassman put it, “You can’t be a friend to somebody who’s studying with you.” Maezumi’s relationship with Glassman was imbued with this formality, yet “in some sense we were like lovers,” mused Glassman. Pat Enkyo O’Hara, who received dharma transmission from Glassman, remembers that once, when she was attending a talk given by Maezumi Roshi, Glassman very lovingly reached over and adjusted his teacher’s robe. “It was such a poignant moment,” O’Hara says. “When they were together, it was very sweet.”

Eventually, Maezumi told Glassman that he was planning to make him a roshi, but Glassman said he didn’t want to use that title. “What do you mean?” asked Maezumi. “What do you want to use?” Bernie, just Bernie, was the answer. But that was a no-go for Maezumi, so Glassman relented: “Roshi” would be fine.

“I couldn’t have hair when I was with Maezumi Roshi and I couldn’t be Bernie,” Glassman said. “Then he died in ’95, and by ’96 I was Bernie again, and I had a beard and hair.” For Glassman, this marked a shift away from the traditional hierarchy of student and teacher. Maybe he was a little further along on the path than his students, but he believed that they were all learning together.

Chuck Lief, former president of Greyston Foundation and now president of Naropa University, says that people always think they know what a Zen master is and isn’t, and Glassman relished breaking these preconceptions wide open. “At night, you’d go to his house,” says Lief, “and he’d have the TV on and he’d be smoking a cigar and eating a corned beef sandwich.” Glassman, Lief asserts, “was the guy that went the furthest to teach and work with people who were least likely to be included.”

Actor Jeff Bridges touring Greyston Bakery, which Bernie Glassman founded to create jobs in the troubled city of Yonkers, New York. Bridges and Glassman were friends and coauthors of The Dude and the Zen Master.

One morning in the early seventies, Bernie Glassman was getting a lift to work with some colleagues from McDonnell Douglas. He’d recently asked Maezumi Roshi a question about reincarnation, but Maezumi hadn’t answered it. That left Glassman in what he called “the powerful space of an unanswered question.” In that space of not knowing, sitting in the back seat of a car, Glassman suddenly had a vision. A vision of hungry ghosts everywhere.

Called pretas in Buddhist cosmology, hungry ghosts are beings who experience (and represent) endless, unfulfillable desire. At first, Glassman saw these suffering, unsatisfied beings outside himself. But then he had the keen sense that there was no separation: he was those beings, they were him. Glassman knew then that his life’s calling was to feed the hungry, literally and figuratively. He could not stay forever holed up in a zendo. He needed to take the realizations won on the meditation cushion out into the world.

In 1982, Glassman and his students opened the Greyston Bakery in Yonkers, New York, a city challenged by unemployment, violence, and drugs. His conviction was that a business could both generate profits and serve the community. This has meant hiring people generally considered unemployable and providing them with competitive wages, medical benefits, and the support they need to actually be successful, such as help accessing child care and safe housing.

So, let this sink in: Greyston Bakery hires without conducting interviews or background checks or even reading resumes. If someone shows up wanting to work, they put them on the list for the next available position. And, contrary to what some might expect, this is no recipe for disaster. Today, the bakery has 176 employees who were hired using their Open Hiring model, and they produce 35,000 pounds of brownies daily. If you’ve ever had a bowl of Ben & Jerry’s Chocolate Fudge Brownie or Half-Baked ice cream, you’ve had brownies from Greyston Bakery.

In 2000, Glassman went to Chiapas, Mexico, as an apprentice with Clowns Without Borders.

In time, Glassman and his team created the Greyston Foundation, which receives the profits of Greyston Bakery. Today, the foundation includes Issan House, which provides permanent housing to people living with AIDS/HIV; community gardens, which produce harvests in excess of seven tons annually; and a workforce development program that offers college prep and job readiness assistance to youth and trains people to work as security guards, home health aides, and more.

As the Greyston Foundation, or Greyston Mandela as it is also called, was being developed, Glassman and his second wife, Sensei Jishu Angyo Holmes, settled in a sketchy neighborhood in Yonkers and held intensive meditation practice periods in the yard of a condemned school, which was also a hangout for junkies. The practitioners put on thick gloves to clear out the discarded condoms and needles and they sat on hunks of broken concrete and old tires instead of zafus and zabutons. “It was an incredible experience,” recalls Joan Halifax, “to practice in this place with boom boxes and shouts and traffic and graffiti everywhere.”

Chuck Lief was always amazed that Glassman never got mugged. “He had a dome of protection around him,” Lief remembers, which was grounded in the totally genuine way he interacted with people. “Bernie was the guy who made the connections with the neighborhood, and there was nothing patronizing about the way he approached the people he worked with.” Social service can be patronizing, with a hierarchy of helper and helped, but, Lief continues, “With Bernie it was never an us-and-them thing.

“From Bernie’s point of view, every single person that engaged in the Greyston project was ultimately capable and competent and worthy of trust and of being at the table. It was a total democracy with a small ‘d’ approach. I’d find people starting to use words like mandala—guys who’d just got out of prison and had grown up in the Christian church. Yet somehow, with Bernie, they became part of the sangha.”

In 1994, on Glassman’s fifty-fifth birthday, he made the decision to establish the Zen Peacemakers Order. Originally, it was intended strictly for Zen practitioners, but it eventually blossomed into an international, interfaith network called simply Zen Peacemakers.

As articulated by Glassman, the community was founded on three tenets for integrating spiritual practice and social action: (1) not knowing, thereby giving up fixed ideas about ourselves, other people, and the universe; (2) bearing witness to the joy and suffering of the world, and; (3) loving action for ourselves and others.

Glassman saw these three tenets as traditional Zen, phrased in a fresh, modern idiom. “In Zen training,” says Glassman, “koan study gets you to experience the state of not knowing.” Then, bearing witness is just sitting meditation, or shikantaza, and loving action is none other than compassion.

At bearing-witness retreats at the extermination camps of Auschwitz and Birkenau, participants sit on the train tracks where victims were brought in on freight cars. They alternate silent meditation with chanting the names of the dead.

In terms of peace and justice work, Glassman explained the three tenets by saying that positive change doesn’t come out of an activist having fixed ideas. What really helps is being completely open and listening deeply.

“When we bear witness, when we become the situation—homelessness, poverty, illness, violence, death—the right action arises by itself,” Glassman said. “We don’t have to worry about what to do. We don’t have to figure out solutions ahead of time. Peacemaking is the function of bearing witness. Once we listen with our entire body and mind, loving action arises.”

Bearing witness is at the heart of the groundbreaking retreats for which Glassman was to become best known: street retreats and retreats held at the concentration camps of Auschwitz–Birkenau.

Street retreats combine meditation practice with living as a homeless person for several days, with no money, no shelter, no job, no usual identity. Retreatants take their meals in soup kitchens and learn to survive without even the guarantee of a bathroom. Pat Enkyo O’Hara has said that the power of a street retreat lies in how it pushes things “right in your face, so there is no way to exclude anything. Living on the street is scary. But the minute you include the fear in your practice, it’s much less scary, because then you can touch the fear, you can feel it, and it’s not this black cloud following you around.”

On the street retreats created by Glassman, retreatants live as homeless people—eating in soup kitchens, begging for money, and sleeping outside. “When we go to bear witness to life on the streets, we’re offering ourselves. Not blankets, not food, not clothes, just ourselves,” said Glassman.

“I had no idea of what I was getting into—and I learned a tremendous amount,” Glassman said of his first street retreat. “For me, part of the state of not knowing is entering into the worlds I am afraid of, entering into worlds about which I have no idea. I’m drawn to those aspects of myself that I do not understand, that I fear, that are a mystery. I’m drawn to enter that realm. If I meditate in an arena which is very familiar to me, then I find that it’s too peaceful. It’s wonderful. It’s like having a cup of cappuccino. I love to meditate. But when I go out into these arenas like the street, things arise that are tremendously important, and there comes a healing of myself and others that I would never have expected.”

As Frank Ostaseski puts it, “Bernie’s street retreats and Auschwitz–Birkenau retreats were ways of going into the darkness and illuminating it.”

Glassman was inspired to hold the Auschwitz–Birkenau retreats after he visited the extermination camps for an interfaith conference. “I walked into Birkenau,” Glassman said, “and I could feel the millions of souls crying out to be remembered. I said I have got to bear witness to what’s going on here. I spent a year and a half creating a format, which involved bringing together people from all walks of life—children and grandchildren of SS members, survivors, children of survivors, people from many countries, many religions.”

During the bearing-witness retreats at Auschwitz–Birkenau, the lion’s share of each day is spent sitting by the infamous train tracks where more than a million victims were brought in on freight cars, alternating silence with chanting the names of the dead. Ostaseski remembers sitting on those tracks with Glassman. “He sat in stillness but it wasn’t distant stillness. It was engaged,” says Ostaseski. “Then the tears just rolled down his face. He really let himself connect with the pain of the people who died there, and were guards there.”

It was on the eve of the twenty-third annual Auschwitz–Birkenau retreat that Roshi Bernie Glassman died.

Bernie Glassman with his wife Roshi Eve Marko. Marko is a novelist and the head teacher at the Green River Zen Center in Massachusetts.

“Bernie taught me more about grief than anyone,” said Joan Halifax at the memorial for him held at Upaya Zen Center in Santa Fe. “What we learned from him is that to turn away from grief is to turn away from life.”

Glassman and his wife Jishu had moved from Yonkers to Santa Fe in March, 1998. Their new home—lovingly chosen by Jishu—was adobe, hacienda-style, and perched over the Santa Fe River. Six days after moving in, before they’d even finished unpacking, Jishu had a heart attack. Four days later, she passed away. Glassman did not hide his grief from anyone and he did not want consolation.

Time went by and Glassman began to feel a shift. From his bearing witness—from his grief for Jishu—she was integrating with him. “When she was still alive, Jishu had brought into our relationship certain energies that lay dormant in me,” Glassman wrote. “Now, with her death, I either had to manifest them myself or watch them disappear from my life. Jishu was not the only one to die on that first day of spring. Bernie died, too. Someone else is now emerging, someone else is coming to life. For lack of a name, I call that person Jishu–Bernie… I still don’t know who that person is or what that person will do. There are many things I still don’t know.

“The third tenet of the Zen Peacemaker Order is healing ourselves and others. But often I think that what’s really happening is more basic than that. When we don’t know—when we let go and sit with shock, pain, and loss, with no answers, solutions, or ideas, with nothing at hand but this moment, this pain, this grief, this absence—then out of that something arises. And what arises is love. I don’t have to do anything. I don’t have to create anything. Love arises by itself. It’s been there all the time, and now, when I’m less protected than at any other moment in my life, it’s there.

Glassman, with his signature red beret and cigar, off in search of Sunday bagels.

“People ask me every day how I’m doing. I don’t know how to answer them; there are no words. So I just tell them I’m bearing witness. It must be hard, they say. No. But isn’t it sad? they ask. Isn’t it painful? No, I say. It’s raw, that’s all. It’s bearing witness, and the state of bearing witness is the state of love.”

Joan Halifax understands that. “For me, this week since Bernie’s death has been filled with grief, beauty, and the loneliness of sorrow. It has also been filled with life, all of life, which includes grief and death,” she said at Glassman’s Upaya memorial.

“Now I, along with many others, sit with the reality that our teacher’s physical life force has been extinguished. Yet his teachings live through so many. We certainly will miss his odd tenderness, his tangled thought experiments, and his raw and real ways. We also know he would want us to stand strong in not knowing, and to bear witness to the joys and sorrows of this world, including our own sadness at his death. And he certainly would want us to meet the world with unfiltered compassion. This was his way.”

After the memorial at Upaya, the mourners feasted together on Glassman’s favorite treats: pizza and Ben & Jerry’s brownie ice cream.