YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

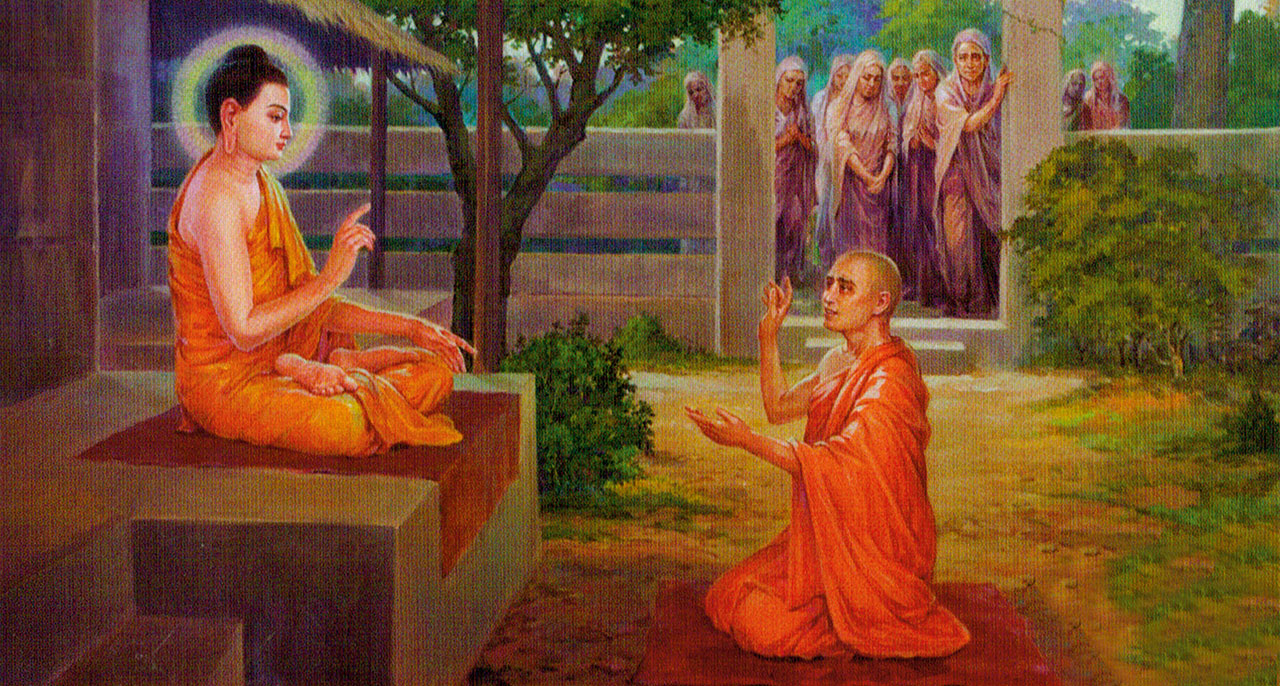

A Thai mural. The Buddha makes the teaching mudra with his hand. Photo by Badbadz / Shutterstock.com

The earliest Buddhist texts common to all Buddhist traditions can be traced back to the fourth or fifth century BCE. After the Buddha’s death, at the council of Rajagaha, a town in northern India, five hundred of his most accomplished monks who’d attained nibbana, gathered and shared his teachings. There, it’s said, Ananda, the Buddha’s loyal attendant, recited many of the suttas (discourses of the Buddha) for he’d spent more than twenty-five years with the Buddha and had an infallible memory.

For centuries after that, the Buddha’s teachings were only transmitted orally, from groups of monks to groups of monks. The Sri Lankan tradition claims that the canon was only written down in the first century BCE due to a fear that there weren’t enough monks at the time to ensure its survival.

The Sutta Pitaka, which is one of the three “baskets” or sections of the Pali canon, can effectively be considered the fundamental teachings of the Buddha. It’s a very diverse and extensive set of texts that includes poetry and philosophy, myths and history, practical advice and humor, grand narratives and pithy sayings.

It’s important to emphasize the oral nature of the Sutta Pitaka (or the canon generally), especially since we now live in a world in which we’ve been expected to communicate with merely 140 characters. As the scholar Sarah Shaw points out, when we hear the suttas chanted out loud, as they’ve been for so many centuries, the rhythm of the semantic and structural repetitions along with the themes addressed, embody one of the fundamental truths of Buddhism: the rising, sustaining, and passing of all things.

Chanting the suttas has a meditative quality that, not unlike today’s guided meditations, guides us through aspects of the teachings. Historically, and still today, the recitation and memorization of the suttas has been seen as a spiritual practice, although only an extremely small number of people memorize the entire canon and thereby earn the title of tipitakacarya, master of the three baskets.

Many suttas start with the phrase “thus have I heard” and state where, when, and to whom they are addressed. With a small effort of imagination, we can picture being in Jeta’s Grove at Anathapindika’s Park, in the city of Savatthi, when the Lion’s Roar Smaller Sutta was expounded, or in the Kuru country, in the city of Kammasadadhamma, when the Buddha taught the Foundations of Mindfulness Sutta, the fundamental teaching on establishing mindfulness, which is still used today for mindfulness meditation. In most cases, the Buddha is the one who teaches, but on rare occasions, others teach, such as his close disciple Sariputta or the nun Dhammadinna, or even devas and brahmas, divine beings that frequently figure in the suttas.

In the Sutta Pitaka, we meet the Buddha in his many facets. He’s a “buddha,” the incarnation of an ideal. He’s an extraordinary newborn infant who walks and speaks at birth and is welcomed by gods and spirits. He’s a prince who gives up worldly desires and possessions to pursue the spiritual life. He’s the just-awakened buddha who glows with his life-transforming realization and astonishes those he meets on the road. He’s the consummate teacher whose words awaken kings, such as Pasenadi; murderers, such as Angulimala; and courtesans, such as Ambapali. And he’s the “beautiful friend” (kalyanamitta) who laments to his assembly of monks that “this assembly appears to me empty now that Sariputta and Moggallana [his two chief disciples] have attained final nibbana.” In other words, in the Sutta Pitaka, the Buddha is both a supernatural being who performs miracles and travels to divine realms, and an ordinary man whose back hurts and whose stomach gets upset.

The Sutta Pitaka offers a window into an ancient world, and while many descriptions are formulaic and fixed, details of an ancient way of living shine through. Reading it, or better even, reciting it out loud, recreates the social, religious, and philosophical world in which Buddhism emerged. Interestingly, this was a world that the Buddha and his followers in some ways challenged and in other ways accepted.

One particular dimension that Buddhism engaged with was the ancient Indian caste system. In the Agganna Sutta, the Buddha questions the Brahmins’ position and ritual purity status in ancient Indian society. In a rather humorous passage, he ridicules the Brahmins for claiming to be pure because they’re born out of the head of Brahma (a description found in the Purusa Sukta of the Rig Veda, an ancient Vedic text). In reality, the Buddha scoffs, the Brahmins are born like everyone else from a woman’s womb. In pointing out this biological fact, considered highly polluting in Brahmanical tradition, he emphasizes that all human beings have impurities and therefore cannot claim any ritual purity, especially ones based on their class. Instead, he teaches that it’s what people do that makes them pure or impure. When beings act out of morally good intentions, they’re pure. When they act out of morally bad intentions, they’re impure. The Buddha concludes, one who has attained nibbana, and therefore acts only out of morally good intentions, is the best among gods and human beings.

Mahapajapati was the Buddha’s aunt and stepmother and a deeply realized dhamma teacher. Here the Buddha is agreeing to ordain her as the first Buddhist nun. “Mahaprajapati Convinces Buddha,” Source Unknown

Although this sutta has sometimes been used as evidence that the Buddha rejected the Indian class system, the Sutta Pitaka as a whole shows that, in fact, he wasn’t concerned with challenging Indian social hierarchy, but only the Brahmanical religious and moral framework. It can even be argued that the Buddhist theory of karma may be used to justify the social, political, and economic status quo, as karma implies that everyone deserves their present circumstances based on past actions. Ultimately, the Buddha merely replaced a religious hierarchy based on birth with one based on monastic status, although one that, in theory, allowed anyone to access this status.

Another dimension Buddhism challenged was women’s status and roles. On the one hand, the Buddha of the Sutta Pitaka advocates for women’s full and active access to the religious life. On the other hand, the texts also betray an enduring negative attitude toward women.

Keeping with the ancient Indian context in which women’s roles were restricted to being wives and mothers, the sangha, the Buddhist monastic community, started out as a uniquely male institution, and indeed women are only marginally present in the suttas.

When women do appear, they’re mostly wives and mothers. For example, in the Uggaha Sutta, the Buddha advised Uggaha’s daughters on fulfilling their wifely duties in the best manner possible—a rather incongruous piece of advice from a monk. In several suttas, he told Visakha, one of his most renowned lay followers, that women achieve rebirths in the heavenly realm of the beautiful devas by—surprise!—also fulfilling their wifely duties.

When Mahapajapati, the Buddha’s aunt and milk-mother, asked him to allow women to ordain as bhikkhunis (Buddhist nuns), he refused at first. But he finally relented when Ananda pleaded her case, pointing out that the Buddha himself had stated that women are as spiritually capable as men of attaining nibbana and that they should, therefore, be allowed to live the monastic life. Faced with the Buddha’s continued refusal, Ananda ultimately appealed to his affections by reminding him that, after his mother’s death when he was still an infant, Mahapajapati raised him, feeding him the milk of her breasts, and for this reason, she should be allowed to be ordained.

The sutta doesn’t reveal which argument won the day, but Mahapajapati and her followers were allowed to become nuns, establishing the female monastic order that has survived to this day in the Chinese Dharmagupta lineage. Although the Theravada bhikkhuni order disappeared by the thirteenth century, contemporary efforts to reestablish the full Theravada (and Tibetan) female monastic orders are slowly starting to bear fruit.

The more than seventeen thousand suttas of the Sutta Pitaka are divided into five nikayas (collections) that are arranged according to length and content. The Digha (long) Nikaya only has thirty-four suttas, but they’re the longest suttas in the canon. The Majjhima (medium) Nikaya has 152 medium-sized suttas. The third section, the Anguttara Nikaya, arranges its more than 2,300 suttas numerically, based on sets of teachings, such as the four noble truths and the noble eightfold path. The fourth section, the Samyutta Nikaya, contains over 2,800 suttas grouped according to common themes and genre.

Finally, the Khuddaka (smaller) Nikaya includes different types of texts, some of which are very ancient, such as the well-known Dhammapada, and others composed later, such as the Buddhavamsa and Cariya Pitaka. The Khuddaka Nikaya also contains the Jatakas, the stories of the Buddha’s previous births. Two important texts of the Khuddaka Nikaya are the Therigatha and Theragatha (the verses from the elders) by the nuns and monks who attained nibbana during the Buddha’s time.

This information might seem tedious, as my students sometimes grumble, but it illuminates the sheer depth and breadth of this collection of texts. It also calls our attention to the extraordinary feat of bringing together and preserving these teachings for over twenty centuries.

Try reading the suttas out loud, slowly and reverentially. Before you start, imagine sitting under the shade of a tree, a man or a woman in ochre robes facing you. They tell you, “This is what I heard. It was the rainy season. We were at Migaramata’s Palace, in the city of Savatthi, and the fully enlightened one, perfect in knowledge and conduct, the teacher of gods and humans, the blessed one, the Buddha taught us about the dhamma, which is lovely in the beginning, lovely in the middle, and lovely in the end.”