YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

It began in the 1980s with the heart-rate monitor.

For the first time, an individual could observe changes in a vital sign as they happened. And they could do it on their own, whenever or wherever they chose, for any reason that made sense to them.

Four decades later, we have rings, watches, scales, and phones that track, measure, and quantify almost every aspect of our fitness, nutrition, and metabolism.

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are the latest step along that path.

By attaching a CGM device to your upper arm, you can see how your blood sugar reacts to your meals.

That real-time feedback, ideally, can help you identify the foods that cause the largest spikes in your blood glucose—along with the crashes that can sometimes follow.

Making better food choices should help you minimize those peaks and valleys.

But does monitoring every rise and fall in blood glucose make sense for you or your clients?

Is there enough value to justify the expense?

We’ll answer those questions as thoroughly as we can, with the warning that research is far behind practice in some key areas.

But let’s start with a more basic question…

Continuous glucose monitors were developed for people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes. The devices typically attach to the upper arm via skin-piercing filaments. They’re kept in place with an adhesive that makes them look like a nicotine patch.

Continuous glucose monitors help people with diabetes identify swings in blood sugar before they cause problems. For those who depend on insulin, the CGM device can help their doctor modify the dose.

It was only a matter of time until people without diabetes began exploring the potential of CGMs to help them meet their goals.

An endurance athlete, for example, might want to know if continuous glucose monitors could help them maintain steady fuel levels.

Someone on a low-carb diet could use continuous glucose monitors to avoid any food that would interfere with ketosis.

And a health and fitness enthusiast—which, after all, includes most of us—might simply want to avoid the extreme glucose spikes that research has linked to a higher risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, some cancers, and death from any cause.1, 2

What started with biohackers buying CGM devices on eBay soon became a growth industry.

Venture-capital firms are betting tens of millions of dollars that companies like Levels, January, and NutriSense will find an enthusiastic market for continuous glucose monitors among health-conscious people who don’t have diabetes.3

Your blood sugar level is usually described as milligrams of glucose per deciliter of blood (mg/dL).

A fasting glucose level below 100 mg/dL is considered normal and healthy. A higher level means you have either prediabetes (100 to 125) or full-blown type 2 diabetes (126 or higher).

But what does that mean? How much actual sugar are we talking about?

Four grams, enough to fill one teaspoon.4

That’s the normal amount of circulating glucose for someone who weighs 70 kg (154 pounds).

That teaspoon of sugar (yes, your body runs on the lyrics to a Mary Poppins song) is dispersed across 4.5 liters (1.2 gallons) of blood.

So when we talk about how much glucose enters your bloodstream in response to a meal, keep in mind that the amounts in question, in most cases, are just a fraction of a teaspoon more than your normal level.

The American Diabetes Association estimates that more than 35 million adults in the U.S. have type 2 diabetes.5

Another 96 million have prediabetes.

If those estimates are accurate, about 50 percent of U.S. adults either have diabetes or are well on their way.

Moreover, the people who have high blood sugar aren’t always who’d you predict.

“We can’t tell if someone’s going to have disrupted metabolic health just by looking at them,” says University of Washington neuroscientist Tommy Wood, MD, PhD, whose research on continuous glucose monitoring was invaluable in writing this article.

“Even in people who’re thought to be super-healthy, we often see impaired fasting glucose.”

For example, in one small study of non-elite endurance athletes, readings from continuous glucose monitors showed that four of the 10 participants had prediabetic blood sugar levels.6

When diagnosing diabetes or prediabetes, doctors look at either fasting glucose or HbA1c, which shows average blood sugar levels over the previous three months.

Neither measure shows how high your blood sugar rises after a meal. We know that big increases in “postprandial glucose”—that is, your blood sugar levels after you eat—are linked to a higher risk of cardiovascular disease. So getting this data completes the blood sugar picture.7

(Scientists and physicians typically look at what happens to postprandial glucose levels for about two hours after a person eats, in order to fully understand how that person’s body responds to carbohydrates.)

In a 2018 study from a Stanford University research team, 25 percent of participants with healthy blood sugar levels nonetheless showed that pattern of extreme glucose variability—big post-meal spikes, followed by dramatic dips.8

Postprandial glucose varies from one person to the next.

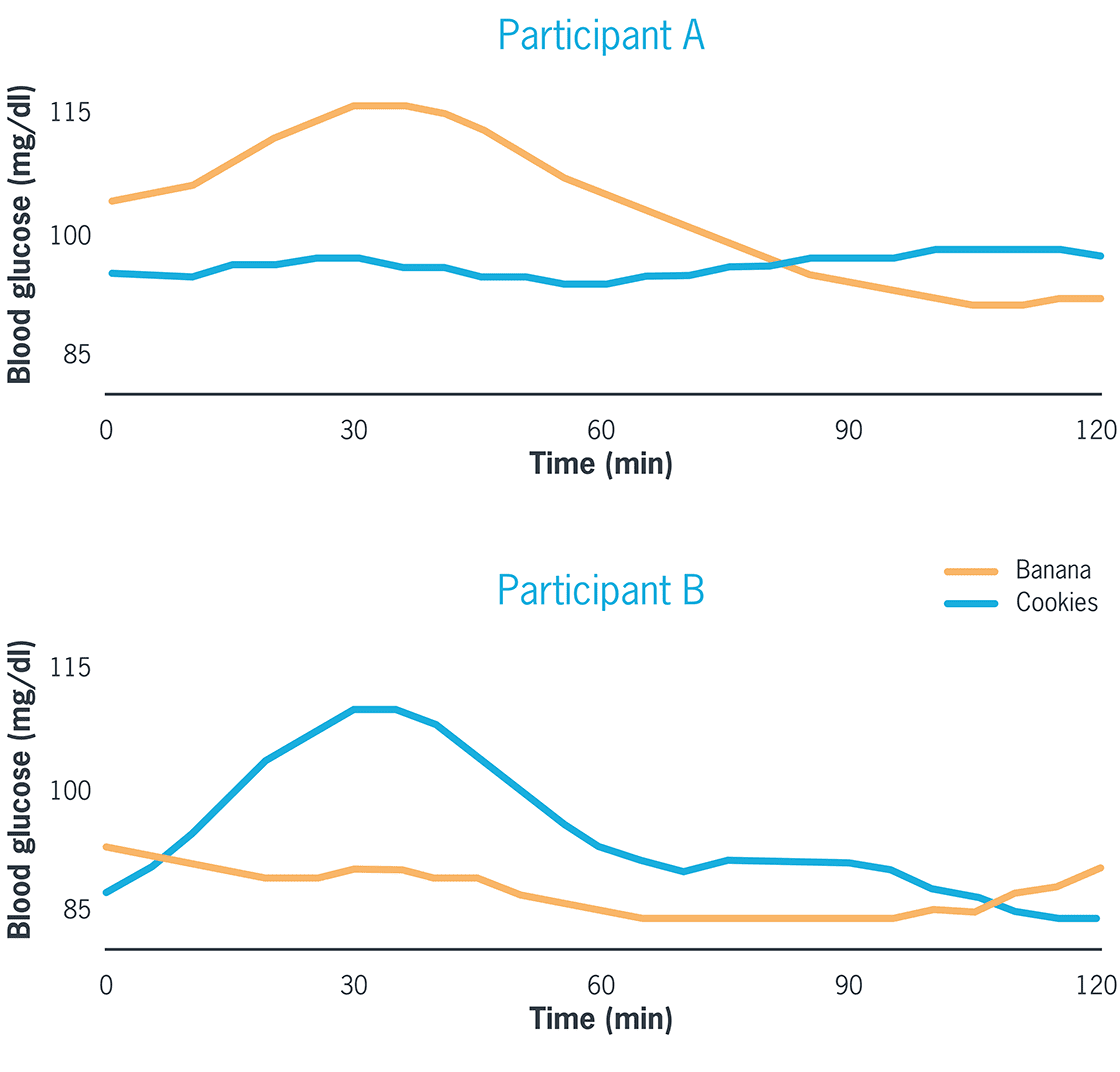

An often-cited paper from an Israeli research team showed that two people can have completely different responses to the exact same food.9

As you can see in this example from the study, one participant’s blood sugar quickly rose and fell after eating a banana, but didn’t do much of anything after eating cookies. Another participant had the opposite response to the same two foods. Their blood sugar spiked when they ate cookies, but fell slightly after eating a banana.

A 2020 study ranked the factors affecting an individual’s glucose response:10

![A chart shows several factors that affect blood sugar response. From the top, the factors read (in order of how much they impact glucose response): Meal composition (15.4%), genetics (9.6%), meal context (7.7%), serum glycemic markers (6.7%), microbiome (6.0%), age (4.6%), serum lipid markers (4.1%), blood pressure (3.6%), anthropometry (2.4%), other serum markers (1.7%), FFQ [food frequency questionnaire, which helps measure the affect a person’s habitual diet] (0.6%), sex (0.4%). (Note: Continuous glucose monitors allow you to see how anything from an individual food to a full meal affects your blog sugar in real time.)](https://assets.precisionnutrition.com/2023/01/BloodSugarResponseChart.png)

This table, adapted from the study, shows that—as you’d expect—meal composition (what you eat, and how much) will have the biggest impact on your glucose response. Meal context—when you eat, and what you do before and after—also matters. (FFQ stands for “food frequency questionnaire” and helps measure the effect of a person’s habitual diet.)

Continuous glucose monitors, like other health- and fitness-tracking devices, can be appealing and useful to some people in some circumstances.

Because they offer objective information, they can serve as a kick in the pants to someone who aspires to exercise more or eat better.

For example, a 2021 study from Colorado State researchers found that fitness trackers motivate inactive people to move more.11

But for some, the novelty effect quickly wears off.

In a study of long-term Fitbit users—men and women who’d used their device continuously for an average of 412 days—two distinct groups emerged:12

Continuous glucose monitors, though, are different from fitness trackers in two important respects:

Levels, for example, offers its members four weeks of continuous glucose monitoring, which costs $199 for two 14-day monitors or three 10-day monitors with Bluetooth capability. That’s in addition to the $199 annual membership fee.

“The primary goal is to see how food affects their health, and to close the loop between diet and lifestyle choices and how they feel,” says Lauren Kelley-Chew, MD, head of clinical product for Levels.

The open question: What does someone do with that information once they have it?

That brings us to the other side of the question of whether healthy people who don’t have diabetes should consider CGM devices.

“Blood sugar goes up and goes down,” says Spencer Nadolsky, DO, a board-certified obesity specialist.

That’s what it’s supposed to do.

But in some corners of the internet, some doctors, gurus, and influencers are telling people it’s not.

Dr. Nadolsky says he’s had patients whose CGM device data caused them unnecessary anguish.

“They were scared when they saw any blip on their continuous glucose monitor,” he says. “It’s actually to a point of pathology because they stress so much over normal glucose excursions.”

Even when glucose excursions go outside normal ranges—higher than 140 or lower than 70 mg/dL—they tend to be short, according to a 2019 study with participants of all ages who didn’t have diabetes.13

The median time in hyperglycemia (above 140 mg/dL) was just 2.4 percent. The median time in hypoglycemia (below 70 mg/dL) was even lower: 1.1 percent.

Carbohydrates are not inherently unhealthy.

Some are healthier than others, of course. In general, most of us would be better off if we ate fewer highly processed carbs and fewer foods with added sugar.

But that’s also true of foods loaded with highly processed fats.

The difference is that carbs will produce a larger increase in blood sugar than fats, creating the illusion that carbs are “bad” and fats are a good alternative.

Taken to extremes, someone might conclude that a piece of bacon is better for you than a piece of fruit.

Why does it matter if continuous glucose monitors feed into that demonization of carbs? Because …

That’s the conclusion of a 2020 study from a team of Harvard psychologists.14

The participants in the study, who had type 2 diabetes, were given a beverage that was labeled as either low sugar (zero grams) or high sugar (30 grams).

Those who thought they got the high-sugar drink had a much larger glucose response than the ones who thought their drink had no sugar at all.

In reality, everybody got the exact same drink, which had 15 grams of sugar.

As the authors write, “Subjective perceptions of sugar intake, even when incorrect, produce measurable biochemical changes.”

“The stress is probably worse for your health than the carbohydrate itself,” Dr. Wood says.

Which brings us to the final reason why it might not be a good idea to monitor your blood sugar if you don’t have diabetes or a high risk of developing it.

“There’s useful information to be had” from continuous glucose monitoring, Dr. Wood says. “But it can also create stress responses around food, particularly around carbohydrates.”

When the stress becomes disproportionate to the value of the information causing the stress, it can lead to some dark places.

“People who have a history of disordered eating or anxiety around diet or lifestyle choices should consider whether having this kind of data is the most helpful tool for them,” Dr. Kelley-Chew of Levels says.

Andy Galpin, PhD, a professor of exercise science at Cal State Fullerton, thinks this point applies not just to CGM devices, but to other types of tracking technology as well.

“My honest intuition is, there’s a lot of people who have a lot of problems when they start introducing tech to their health,” he says.

He mentions orthosomnia—a word researchers coined to describe people who become obsessed with achieving “perfect” sleep, based on data from their sleep tracker.15

So far, there’s little evidence that trackers are linked to better health outcomes.

Yes, some people who use fitness or nutrition trackers do lose weight or get more exercise. But it’s not yet clear if those changes lead to measurable improvements in their cardiovascular or metabolic health.16

Keep in mind, this is what we know (or don’t know) from published studies. Scientific research always lags behind what people do in practice. Some individuals will have years’ worth of personal data before researchers can show us if those results are typical over time and across populations.

Even then, each of us will interact with the technology in our own ways.

“Data can be freeing, divorcing choices from emotional labels, and giving you objective feedback to work with,” Dr. Kelley-Chew says.

“But if it’s not helpful, there are plenty of other steps one can take to work toward better health.”

Whether a continuous glucose monitor, or any technology, works for you will depend on your goals, mindset, and personality.

Here are three questions to help you make the best choice:

“If you did two weeks of continuous glucose monitoring, maybe you identify something you eat regularly that you thought was pretty good but caused a big spike in blood sugar,” Dr. Wood says.

“You’ll be like, ‘Okay, maybe I’ll eat less of that.’ That’s useful information to have.”

Dr. Galpin agrees.

“Some people will be excited about having the new information,” Dr. Galpin says. “It might be worth it to know something about their health, or to make sure they don’t have a problem with glucose.”

Both believe the person without diabetes who’s most attracted to the idea of continuous glucose monitoring will be the least likely to get anything out of it.

“They’re healthy, affluent, and have access to the best healthcare,” Dr. Wood says.

That describes the pro athletes Dr. Galpin works with one-on-one. But that doesn’t mean continuous glucose monitors are useless for him as a coach.

If an athlete is overly focused on their metabolism or their sensitivity to carbs, a CGM device can help rule those things out.

“Rather than finding, like, ‘Oh my God, carrots smash your blood sugar,’ it’s generally been, ‘Like I told you, you’re fine. It’s not your blood glucose,’” he says.

That frees up the client to focus on things that matter more to their performance and health. (BTW: Our Level 1 Nutrition Coaching Certification gives you the knowledge, tools, and skills to help people achieve the results they really want.)

Experts who express skepticism about CGM devices for folks without diabetes have a consistent concern: that people will read way too much into the data from their continuous glucose monitor.

“Blood glucose is easy to measure and understand, so people focus on it, like the person looking for their keys under a lamppost,” says obesity researcher Stephan Guyenet, PhD, author of The Hungry Brain.

Looking at how specific foods affect your blood sugar doesn’t help you understand why you’re eating those foods in the first place.

For that, you need a much deeper understanding of how your eating behaviors are influenced by your environment, and how to modify them when you feel they’re affecting your health.

Sometimes the best strategy is simple acceptance.

For example, if you know a piece of cake will spike your blood sugar, and you also know you’re going to eat it anyway, “just enjoy the cake,” Dr. Wood says.

Dr. Kelley-Chew has a similar perspective.

“Eating a dessert and having a blood sugar spike is not going to ruin your metabolic health,” she says. “Your body knows how to deal with a surge of glucose.”

Back in 2017, Dr. Galpin coauthored a book called Unplugged, which cast doubt on the value of all the information we collect from fitness- and performance-tracking technologies.

The authors argued that the human body is not a weather report or baseball score. It’s too complex to be assessed by a single number or metric.

“I’m a proponent of people learning and understanding their body better,” Dr. Galpin says. But that doesn’t mean you need to jump on every new tracking technology.

“You’re going to find about the same answer with all of them,” he says.

The challenge today isn’t collecting answers. It’s finding a way to interpret and put them into context. Once you do, the information you glean from wearable tech provides becomes powerful.

That’s especially true of continuous glucose monitors.

“Obviously, if you have an apple and your blood glucose jumps to 250, that’s not good,” Dr. Galpin says.

“But what about 125? Is that cool? Or 130? Or 140? Like most things in this field, it’s all about context.”

Click here to view the information sources referenced in this article.

You can help people build nutrition and lifestyle habits that improve their physical and mental health, bolster their immunity, help them better manage stress, and get sustainable results. We’ll show you how.

If you’d like to learn more, consider the PN Level 1 Nutrition Coaching Certification.