YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

Thay didn’t speak about peace. He was peace. He didn’t speak about contentment. He radiated contentment. He didn’t speak about love. He embodied love. To be in his presence was a tangible, visceral experience of love.

Once Thay’s attendant invited us to tea with Thay. She said there would also be a movie star and his family who wanted to meet him. We were served tea and sat in silence for some time until Thay indicated that it was a time to speak.

This gentleman said that he had success, fame, recognition, and a beautiful family, yet he realized he wasn’t happy. Thay nodded his head and sipped his tea. He then asked, “Have you ever watched your children sleeping?” “Yes,” he said, “ I love to watch them sleep. They are so beautiful.” Thay said, “Yes, they are so beautiful. Sit with this.”

Later he said, “Sit with the goodness that is present in your life.” And we sat with this.

In the late 1990’s the home of my partner Larry and I was bombed by an unidentified arsonist. We heard the police suspected a white supremacist group that was targeting interracial couples. I was in the house at the time and miraculously escaped the blazing inferno that was once our home. We immediately made plans to spend a month at Plum Village.

There, Larry and I sat in silence with Thay at breakfast. Tears streamed down my face for a half hour. Thay then asked, “Is your dog okay?” We said yes. Thay said, “I am sorry this happened.” Ten minutes later he said, “And it did.” After ten more minutes of silence, he said, “You have a lot of work to do in the United States.”

I felt seen, accepted, loved, and encouraged to do the Great Work. The “I am sorry” was very important to hear and receive, and so was the “and it did.” This brought me right into the present moment. I left Plum Village determined to do the work of releasing the fear and being brave for myself and for all beings.

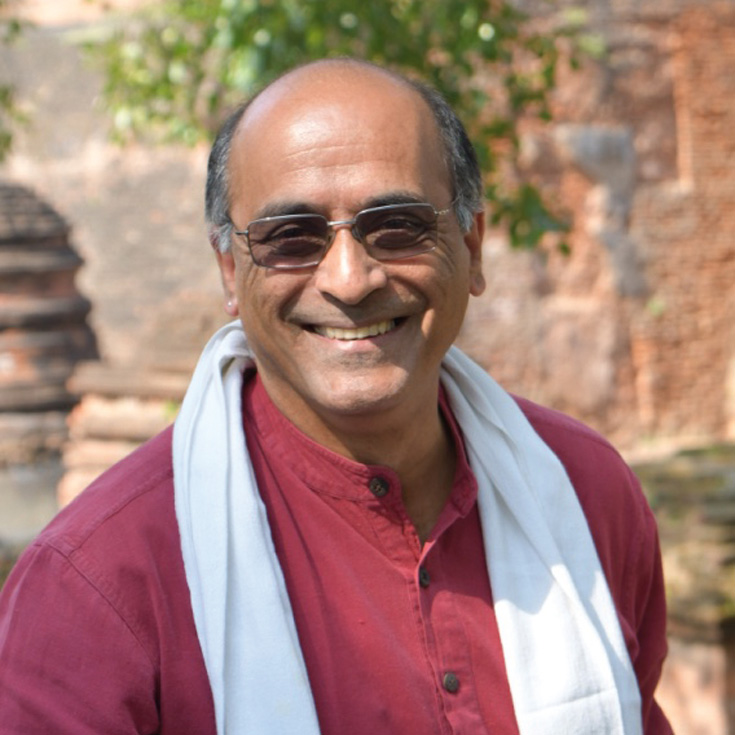

I first met Thich Nhat Hanh in 1987 at the Ojai foundation in California. I don’t think he noticed me much during the retreat, but as we were seeing him off, he looked directly at me and said, “Bring the good buddhadharma back to India. A way of practice that will help people suffer less.”

I returned to India a few months later, and on an impulse wrote and offered to host him should he ever want to visit India. To my surprise and joy, he asked if I could organize a Buddhist pilgrimage to India for him and thirty of his students.

For thirty-five days we traveled through Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, home to many of India’s most famous Buddhist pilgrimage sites. He’d just finished writing his biography of the Buddha, Old Path White Clouds, and at each of these sites he brought the Buddha alive to us.

It was wonderful to experience the stories and drama of the Buddha’s life through Thay’s eyes. Thay was like a happy, curious child meeting his teacher the Buddha everywhere he traveled: meditating in the same caves and rocks the Buddha may have sat on, crossing the same rivers, eating the same food, greeting children who may have descended from children the Buddha met.

Thay’s favorite place was Vulture Peak, the hilltop in Rajgir where, it’s believed, the Buddha loved watching the sunset and taught the Heart Sutra. Thay said his own buddha eyes had opened there some years before, and it was there, on our pilgrimage, that he ordained his first three monastics and transmitted his lay teachings on the fourteen mindfulness trainings and the five precepts.

Sitting under the trees, Thay expounded on the Buddha’s teaching that nothing is born and nothing dies, that there is neither being nor nonbeing. Later, he held my hand and pointed to the turban on my head, saying, “Shantum, the matter of transcending birth and death is as urgent as if your turban is on fire.”

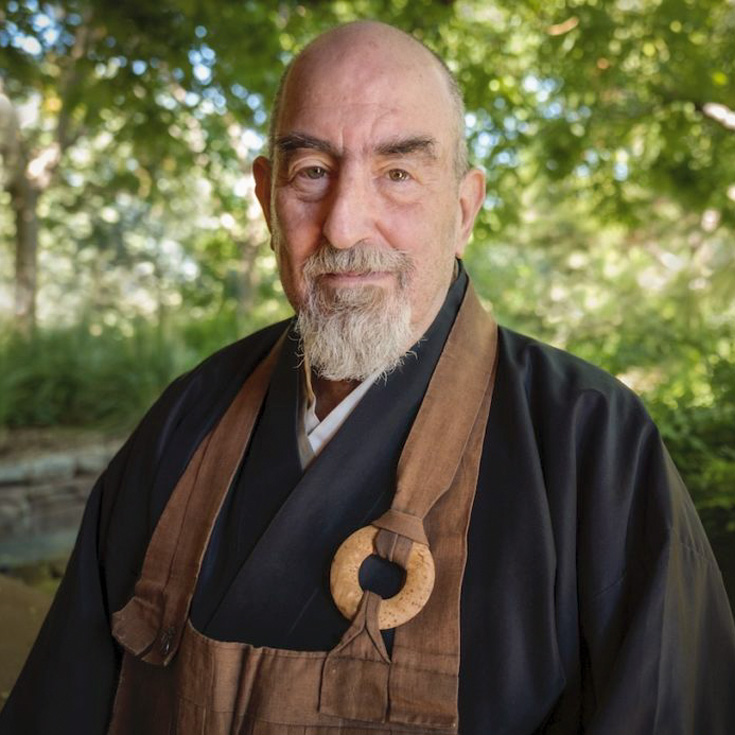

Thich Nhat Hanh wore the simple brown robes of a monk. He walked and spoke mindfully. But the strength of steel lay just below his placid surface. It made him a kind of Buddhist revolutionary.

As director of the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, I organized a talk by Thay in April 1991, in Berkeley, in the immediate aftermath of the first U.S. war against Saddam Hussein’s Iraq and the police beating of African American Rodney King in Los Angeles.

I was struck by Thay’s comments that night. He spoke of his deep anger over the war and the beating of King. Both triggered in him painful memories of the war in Vietnam and the brutal ignorance of U.S. oppression there. He said he had considered canceling his American tour, with all its retreats and dharma events.

His words revealed to me that he wasn’t an unreachable saint, but a man with raw feelings. Then he shared that he’d meditated on his own reactivity and realized that he had to continue his tour as planned, because these oppressors and victims—the police, Rodney King, U.S. soldiers, Iraqis, and all their government leaders—were neither different from nor distant from him.

This insight about interdependence, famously described in his poem Call Me by My True Names, is what I have learned from Thich Nhat Hanh. It has infused how he taught and walked in the world, but it was not a special vision of his own. Such insight appears to spiritual teachers of all lands and ages. It comes from poets and seers. As Walt Whitman wrote: “I am large, I contain multitudes.”

Let us strive to be like Thay was. That is, let us strive to be truly human, our true selves.

I can say that the soft whisper of

his voice in the dark night of confusion,

fear, and violence calls us home to

our True Selves.

I can say that his Teaching brings

the dharma rain and I invite all

of us to bathe in its healing waters.

I can say that his gentle footsteps

upon the earth bring the winds

of peace, the thunder of compassion,

and the powerful moonlight of understanding.

I can say that I have been Graced

to enter the stream of awakening,

finding the Sun of Love in my heart

and the Miracle of Mindfulness in my very breath.

I can say that he tirelessly

engages with this whole being in the

noblest of callings, healing and

transforming the breaking waves of our shadows.

I can say that I have seen

my teacher because he

has caused the Noble Teacher

in me to wake up, to wake up, to wake up.

I can say that his practice,

prose, poetry, and pedagogy

speaks with the clarity and honesty of the Buddha within.

I can say that on this very day

We are blessed to be everywhere with him

and to be here together in this holy moment

witnessing no coming and no going.

Soon after I was ordained by Thay as a novice nun in 1999 I began to have difficulties with an elder sister. This nun had gone through a lot of suffering and could sometimes be harsh in her speech. This was quite painful for me, and I struggled with the situation as a new member of the monastic community.

As novices we were fortunate to have the opportunity to be Thay’s attendants when he would come to teach at our hamlet of Plum Village every other week. While Thay needed very little, it is customary in Asian culture for students to show care for their teacher as a way to learn from them more closely. So two of us novice monks or nuns would start by cleaning his room before he arrived and then spend the day with him. Besides helping him, it was a time for Thay to get to know us and guide us in our practice.

Somehow, he knew that I was going through a hard time with this sister. In a quiet moment after lunch, while he was gently swinging in his indoor hammock, where he often liked to rest, he looked at me and said softly, “You know, other people are the path.”

He didn’t say much more, but I received what he was trying to teach me. That our relationships with other people, especially the difficult ones, are the very path, the conditions that help us learn to be more free. Thay often taught us that living in community was like washing a bunch of chopsticks after a meal: you rub them up against each other and they clean each other. The abrasion is painful, but also transformative.

His simple teaching that day has stayed with me ever since as an important reminder that learning to work with difficult interactions is the very purpose of the Buddhist path, and not some mistake. It is one of the many beautiful and life-changing teachings he offered that I am so grateful for.

In the wide response to Thich Nhat Hanh’s death, I am reminded how immense (and wonderful) the influence of Buddhism has been in North America in recent decades.

It’s not easy to quantify, because a lot of people were moved by a talk, a book, a retreat, but don’t think of themselves as Buddhists or wouldn’t be recognized thus by others, but were nevertheless realigned by Buddhist values, teachings, role models, possibilities. Sometimes they didn’t even know from what lineage that liberatory perspective came, but something was let go or welcomed in or reimagined. Nonattachment, perspectives on suffering, compassion, bodhisattva vows, mindfulness let someone be better to themselves or others or understand the world as codependent arisings and constant change.

There is a subject I keep coming back to but find, again and again, is too vast to describe. It is the deep and subtle changes in values, beliefs, and priorities in many parts of the world in recent decades. It is profound. There are pieces of it that can be named—human rights, feminism, disability rights, environmentalism, anti-capitalism, mutual aid, to name a few things off the top of my head—but they’re just tributaries of a great broad river of change. We are not who we were not long ago, and that’s good news.

when i first met you

you awakened something deep inside of me

the wisdom of spiritual and blood ancestors

the hope of future generations

when i came to study with you

absorbing your teachings

in the Dharma halls

i cried every day

tears of a heart opening

more than i ever knew possible

when i am at my best

i imagine you

walking with my body

speaking with my voice

when i am at my worst

i invite you to sit with me

breathe with me

and hold the fire of my anger

the weight of my broken heart

dear Thay, dear Teacher

i know you are in me

no you,

no me

now it is our turn

as your students

to continue you

it feels like such a heavy responsibility

but i know you believe in us

dear Thay, dear Teacher

may you be free

may we awaken together

again and again

for a thousand generations