YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

This story is proof positive that the arts can bring diverse cultures together. When Parisian artist Maryse Allard came across a book about traditional Korean bojagi textile art, she knew it was her artistic calling. And even though the book was written in a foreign language, she immediately understood and connected with the images of bojagi’s transparent beauty.

Korean bojagi (sometimes referred to as ‘pojagi’) has existed for centuries. The word bojagi means ‘clothes for things.’ Fabrics are pieced together, typically in a square shape, using special seams and sewing techniques. The bojagi is then wrapped around everyday objects, including food, books, jewellery and gifts. Korean folklore believed something wrapped protected good luck.

Maryse pored over books and whatever else she could find to learn the inner workings of bojagi. And her efforts have paid off with friendships across the globe, a trip to Korea and recognition as a leading bojagi artist.

Maryse is kindly sharing her international journey, as well as how she’s put a Parisian spin onto a rich Korean stitch tradition.

Maryse: I discovered bojagi through a book written in Korean. I was fascinated by its transparency, lightness and elegance. And I enjoyed the importance of colour and its symbolic meanings.

I was also impressed with the respect and appreciation the bojagi art form is given in Korea. In France, textile art is not fully considered to be an art, so I wanted to promote the beauty of bojagi in France and create a sort of bridge between our two countries.

I continued to research bojagi techniques and am completely self-taught. I was eventually able to visit Korea to see the revered art form in person, and it was incredible. I met a lot of Korean bojagi artists, and as our friendships grew, I was invited to exhibit.

I was especially honoured to be invited by Chunghie Lee for a solo exhibition at the Korean Bojagi Forum in 2018. Chunghie is a very famous bojagi artist who created the Forum. I’m also very proud to have one of my works permanently exhibited in the Chojun Textile & Quilt Art Museum in Seoul.

In 2012, I started teaching bojagi workshops in France, and I’m now teaching internationally. I can’t believe where this beloved art form has taken me. I’ve met so many sweet and interesting people. Some of them are like sisters to me, and it’s wonderful to be a part of the bojagi family.

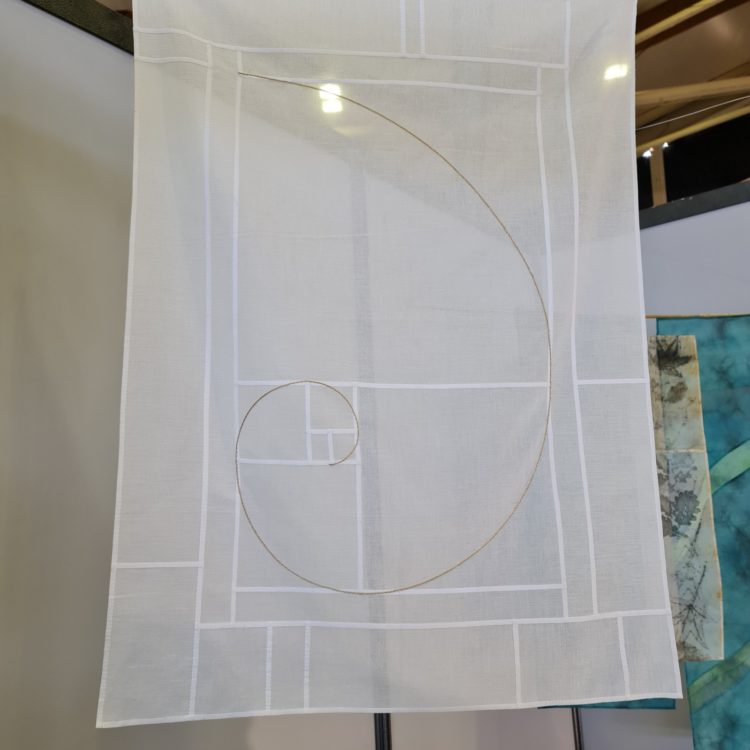

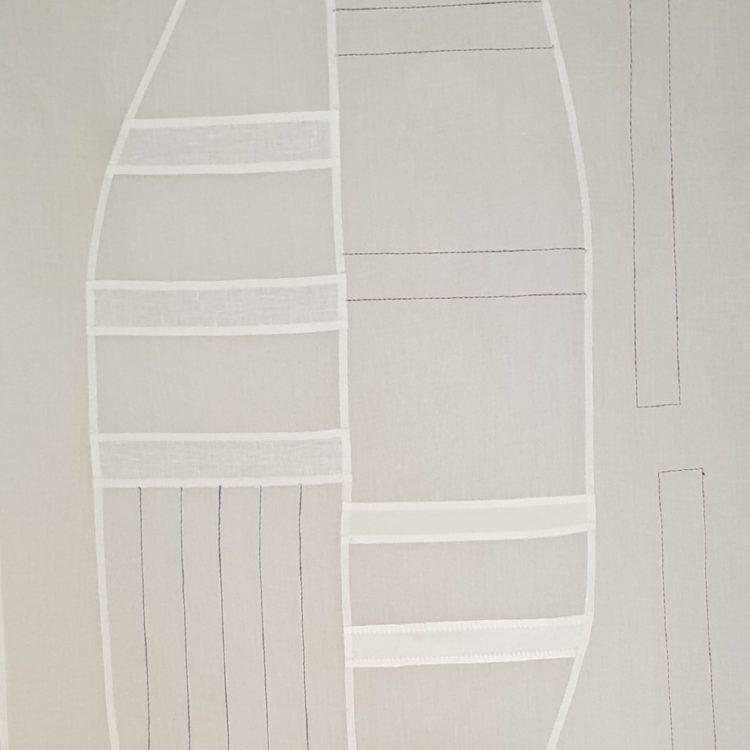

Korean bojagis are traditionally created in a square format, so that’s the shape I worked with first. My Cathedral Window piece is a good example, as well as Log Cabin in which I combined the classic Log Cabin patchwork design into the bojagi.

Since then, I have created bojagi in a variety of shapes, as Korean artists have done the same. I recently saw a 3-D bojagi at a Korean exhibition that I found very interesting and would like to explore.

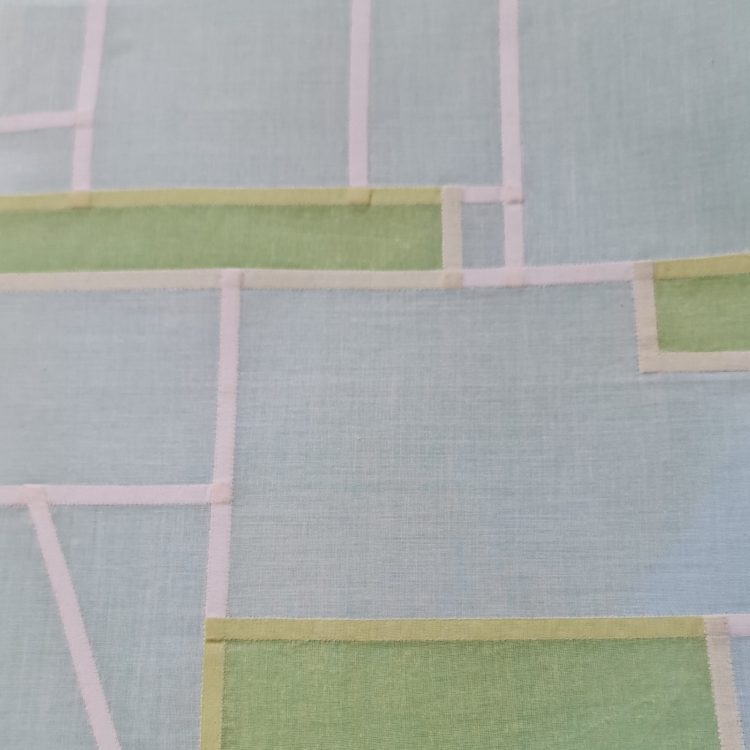

Fabric choices were definitely a challenge at first. I didn’t have any special Korean fabrics, so I worked with French and European fabrics like cotton, silk organdy, linen and batiste. I love organdy for its lightness, as well as linen and silk for their living appearance.

I mostly use new fabrics, but I keep all the leftovers in a box and have made some bojagi or clothes with them. I once bought some old silk at a Seoul flea market. And I’ve sometimes used fabric from old clothes, including scraps from one of my daughter’s wedding dresses.

I especially enjoy working with transparent fabrics. They fool the eye: sometimes you see them and other times you don’t. I encourage readers to not be afraid of working with transparent fabrics. You can always add starch to make them easier to handle.

But I also use plain fabrics that are more translucid than they are transparent. Plain cottons, silk and even batik fabrics can work. The key is to use fabrics that appear the same from both sides.

Mixing different fabrics can also lead to very interesting outcomes. I like transparent places closer to thicker fabrics.

I find inspiration everywhere. And my tastes are rather eclectic. When I’m out walking, I’m inspired by building elements, such as windows, doors or curtain colours. I also love to visit exhibitions in Paris and beyond. Caravage is a favourite. I love the atmosphere and colours in his work.

I love to create, and I’m always surprised at what I make. I mostly see a project in my mind before preparing. I do ultimately use a sketchbook to note some designs, but the image in my mind is most important.

I prepare different colours and kinds of fabrics, but ultimately, they end up choosing me. And my original design only serves as a reference, as I mostly let my work develop intuitively. It may take me a week before I make final choices. My designs mostly depend upon the effect I want to create.

I prefer working with plain colours of fabrics because the seams are easier to see. They create an appearance similar to a stained glass window, and the plain colours give my work a stronger and more pure character.

Korean bojagi artists tend to use many colours. And those colours have traditional symbolic meanings connected to the concepts of Yin and Yang and the Five Elements of the Universe:

yellow (centre/earth), blue (east/ground/yin), white (west/metal), red (south/fire/yang) and black (north/water).

I love Korean artists’ use of colour, and I have experimented with colour as well. But my mind and personality seem to connect more with a neutral colour palette.

I don’t create templates as with traditional patchwork quilting. I just cut as I go and try to stay as close as possible to my design. Sometimes I’ll create a template for curved lines but again, they mostly serve as a suggestion.

Sizing can be a challenge when cutting out blocks for a bojagi. For example, if you plan to have a 5mm fold on the edges, any fold that is more or less than that number will change the overall size of your project.

And because the blocks are joined at a 90-degree angle before sewing, you may lose even more. That’s why it’s important not to cut all the pieces beforehand. I cut them as I go, so I can adjust the size as needed.

Folding the edges of the blocks is also very important. My most important tools are a small transparent ruler with indications of 5mm (or ¼”) and a folder to mark the folds on the fabric. I love my tools because I bought them in Korea.

I also prefer using natural fabrics versus synthetics, as natural fabrics are easier to fold.

Bojagis can be sewn by machine or hand. My first bojagi was sewn on a machine to learn the technique. But I switched to hand sewing because I liked how it breathed…over, under, over, under, etc. Hand sewing also allows me to reflect on my materials and colour choices. It’s all a form of meditation.

Seams play an important role in creating bojagi. I prefer using a flat felled seam with whipstitch because it is very neat and pure. Since only the lines of the bojagi are visible, I whipstitch on the edge of the fold. I stitch as consistently as I can using the lightest colour thread possible.

I also like using a flat felled seam with running stitches, which can be easier for beginners. Those stitches are more visible, so it’s an opportunity to play with contrasting colours.

Sometimes, I’ll even mix the two techniques. But it’s critical to make sure they are folded exactly the same way.

I use a variety of threads for different stitchwork. For whipstitching, I use very thin cotton threads. Quilting threads are too thick. I especially love threads from the French brand Fil à Gant au Chinois. But any good quality polyester or silk thread can work too.

For running stitch, I use a variety of threads, and they don’t have to be thin. Embroidery threads, metallic threads, regular sewing threads, they can all work. But I do tend to only use one colour across a single work.

I was born in Brittany, France. My father was a Navy officer and I spent most of my youth near the sea. For that reason, I love sailing and have been practising for a long time. I am fascinated by the sea’s waves and colours.

Growing up, I always watched my mother and grandmother sewing, knitting and embroidering. My grandmother’s embroideries were especially beautiful. They both taught me a lot, but because I’m left-handed, I had to adapt the tools and stitch directions. It was also difficult to use big scissors.

I loved to make clothes for my dolls and a lot of bags for myself. Fabrics were wonderful to me, especially sweet old linens. I’m very sensitive to fabric textures even to this day.

I came to Paris in 1971 and pursued my studies there. After earning a Spanish degree, I worked in the export business selling perfume and helicopters all over the world.

After having three children, I volunteered around school and their activities. I also started creating collections for home and decoration with a group of several women.

If I had to pick a favourite work, my first choice would be Feathers. It was my first large bojagi, and I learned so many techniques putting it together.

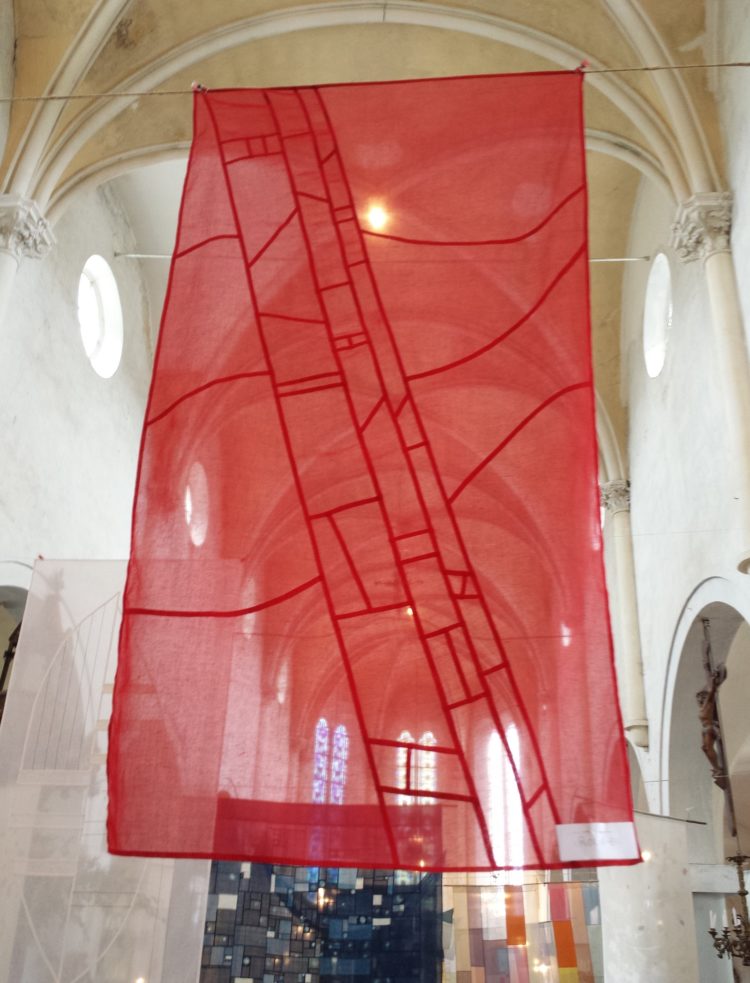

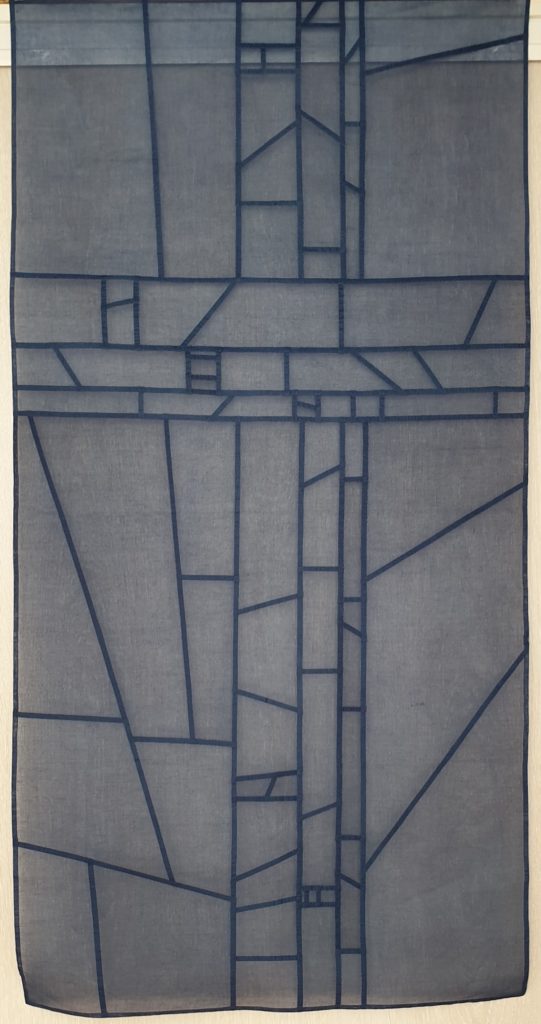

But I created three separate pieces that are also very dear to me in response to the horrible attacks in 2015 in Bataclan, Paris (2015). Each piece represents one of the three colours of the French flag (blue, white and red).

The blue work called Blue Cross features a strong and bold cross, while Red Path has a quiet patch between the curves. The white work called White Nest features a kind of egg or boat in which one is protected. I also used white fabric from my family in this piece.

These works aren’t meant to be political. They are more so about my being a proud French citizen, especially during times of crisis.

Maryse Allard lives in Paris. Her bogaji work has been exhibited at the Chojun Textile & Quilt Art Museum (Seoul, Korea), and she has taught workshops across Europe, Japan, Korea, Russia and Turkey. Maryse also published an instructional book entitled Le Pojagi: Art du Patchwork Coréen (Korean Patchwork Art).

Website: maryseallard.fr

Facebook: fr-fr.facebook.com/maryse.allardleroux

Instagram: @maryse_allard_pojagi_paris/

If you like the Korean bojagi technique, you might also enjoy ‘Katazome,’ a Japanese form of printing using a rice paste resist. Sarah Desmarais seamlessly blends this technique with her interest in repeated patterns derived from nature.