YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

I’m going to try to convince you not to be a jerk. I mean, you’re probably already not a jerk. I’m sure you’re usually basically a very nice human. But if you’re anything like me, you’re usually a nice human who flips out sometimes, says things he doesn’t mean, or maybe even says things he does mean and then encounters the rippling layers of consequences of those things down the line. My goal is to persuade you to do less of the jerk-like stuff you might be doing in your everyday life, and more of the prosocial, happy-making stuff you’re probably also already doing.

Please take a minute and think of a real jerk. This could be a stupid terrible jerk from your present life. It could be an awful disgusting jerk from your past. Maybe even a historical jerk or a bigtime political jerk. Whoever this jerk is, just make sure they really embody jerkiness for you.

Got your jerk? Good. Now, I’d like you to start to catalog this person’s badness. In other words, what makes them such a jerk? Please think of all the qualities that make this individual particularly unbearable. What makes them terrible? What is it about them that makes you want to ring their neck or flee the building?

Let’s look together at that compendium of jerkdom you just assembled. What exactly was on that list of unforgivable attributes this particular jerk personifies? My guess is there are all kinds of things. This person talks behind your back. Or they threw sand in your eyes when you were ten. Or they’re racist. Or just plain damned ignorant. Or a horrible bore who won’t let you get a word in at parties. Or they’ve done something truly terrible to you or someone you love.

A jerk, put simply, is someone who causes harm. They cut you off in traffic or talk on the phone really loud in coffee shops or threaten the democratic norms you’ve always believed were intrinsic to the functioning of a civilized society. That’s why we don’t like jerks. Because they trigger avalanches of chaos everywhere they go.

But here’s the kicker, a time-honored semi-Buddhist insight: all of us have a little jerk living inside us. The part of us that wants what it wants, that doesn’t care about others’ feelings, that’s totally going to snag that parking spot outside the grocery store even though the mom with two kids so obviously got there first. If we want to be happy long term, with flourishing friendships and a more-or-less stable sense of purpose, we’ll need to stay alert to that self-sabotaging part of ourselves, and choose something different.

I lived in a Zen monastery for six years. When I tell people I lived in a Zen monastery in the remote mountains of Colorado—when I show them pictures of the Japanese tea house and the black meditation cushions all in a row—they usually say something like “That must have been so peaceful.”

Yeah, no. It wasn’t. A monastery is a training ground. You’re up at 3:30 in the morning. You’re meditating for hours every day. There’s no personal space. You don’t get days off. All of you are stuck together in your black robes and your weird habits for months at a time.

Enter Anthony. Anthony owned a bookstore in the Mission in San Francisco. He was a longtime Zen student, in his fifties, with a crew cut, a bag full of government conspiracy theories, and an excessively short fuse.

When Anthony came to the monastery, he had the misfortune of being under my auspices. I was the work leader—a position that entailed me, at twenty-five, telling everyone else what to do. Not that I was particularly dictatorial. But busy, for sure. And a little visionary sometimes. There was stuff to get done and I had a plan and I wanted people to step to the vision.

So I ran my meetings like clockwork. I admit it, there were spreadsheets. There were timelines. There was building frustration on my part, since the actual world was, very often, not conforming to my spreadsheets and my timelines.

It all came to a head on a crystalline February day. Thirty strapping volunteers from a local college were on their way to campus. We were going to do fire mitigation—a pressing concern for the monastery, since our surrounding desert mountains were a tinderbox of brush and low branches, just waiting to go up in flames.

I’d arranged for three professionals to arrive with their chainsaws and for each available member of the monastic community to lead a work group of five college kids. I was in the middle of downloading the vision, psyching up the troops, clarifying the details, when Anthony raised his hand.

“Yes, Anthony,” I said.

“What time is lunch?” he said.

I was flummoxed. Lunch? We were about to move mountains!

“Who cares?” I said.

Then I went back to explicating the hauling routes and assigning the responsibilities.

After the meeting, I was walking into the kitchen when Anthony came from behind, spun me around by the shoulder, and threw me up against the wall.

Suddenly, everything went very slowly. I noticed that his face was a startling shade of red, almost purple. There was a single bead of sweat on his forehead. And his breath smelled like coffee and milk.

Anthony shook me and slammed me, saying things like “If you ever talk to me that way again, I will cut your throat.”

Already my mind was tracking back over the last several minutes. Clearly, I had done something that really pissed Anthony off. At first I was a little too dumb to know what it was. I soon realized it was that moment I’d blown off his question about lunch.

Simultaneously, I saw there existed a whole range of options before me, almost like radio stations. Except instead of choosing between NPR and classic rock, my mind started flipping through disparate cultural scripts, little memes that might be appropriate for just such an occasion. I’m from New York, and the New York radio station was enticing me to throw a punch. Thankfully, the Buddhist radio station also clicked on even stronger. I saw how I had come into the meeting all jazzed up, a little manic. I saw how my empathy in the meeting was low. I saw how I had needlessly insulted Anthony, made him feel small. I saw my low empathy and subsequent belittling as the cause of the present death threat.

So I relaxed. “Anthony,” I said. “I messed up. Sorry. Just one of those days.”

He looked confused for a moment. Then I watched his face cycle through its own range of emotions—watched him try to remain angry, then confused again, then sad, then just tired. He dropped my shirt and walked away.

I wish I could say I always have that level of insight. The truth, though, is that spiritual progress is a bumpy road. Not so much an ever-upward line of transcendent growth. More like a series of peaks and valleys. In which you fall flat on your face in the valley. In a swamp. With mosquitoes. And no bug spray. Then dust yourself off and keep working at it.

You can do this meditation in five minutes, if you’d like. I definitely recommend this meditation to anybody who could use a little more kindness in their life. And that’s pretty much all of us.

Let’s start by finding a comfortable posture, either sitting or lying down. Obviously if you’re reading this on a computer or your phone it’ll be hard to close your eyes. So you can keep them open. Or read a few sentences and then close your eyes. Don’t worry too much about whether you’re doing it right. Don’t worry too much about being a great meditator. In fact, just don’t worry too much.

Now let’s bring a warm awareness to your body. Just feel your body. With a sense of friendliness, a sort of grassroots kindness. Feel your hands. Feel your feet.

Bring that warm awareness to the area of your heart. Notice any sensations in the heart area—throbbing, humming, tingling, numb, whatever. Start to notice any emotions that might be here, in the heart. Just kind of take the temperature. Get a sense of things.

You don’t need to get rid of anything, don’t need to feel differently or better. If you’re numb, you’re numb. No problem. If you’re sad, that’s how it is. Angry? That’s okay, too. Often we’re a whole bunch of things all at once. Which is also not a problem.

Now from this sense of the heart—of just being with your heart—let’s call up an image of a good friend. Someone you like. They’ve got your back. Sure, they tick you off every once in a while. But essentially it’s a good relationship—all in all, you want them to be happy.

Now let’s lean a little into this sense that your friend wants to be happy. Just like you, just like everybody, he or she or they really want to be happy. They want to be safe. They want to be healthy. They’d like some peace.

And now let’s just begin to wish them well, using some traditional phrases.

May you be safe.

May you be happy.

May you be healthy.

May you be peaceful and at ease.

Just continue thinking about your friend, repeating these phrases silently to yourself. Maybe after some time, you can imagine your friend filling up with happiness. Imagine your friend getting lighter. Imagine your friend getting happier. Imagine them smiling. Filled with joy.

It’s great to start with a friend when you do this at first, somebody who’s pretty easy for you. Once you get the hang of that, though, it can be really helpful to bring this same kindness, this wishing well, to yourself. May I be safe, may I be happy, etc. Then you can extend that general caring out to people you don’t know so well, and even to people you don’t like so much, and then to everyone, everywhere, without exception.

♦

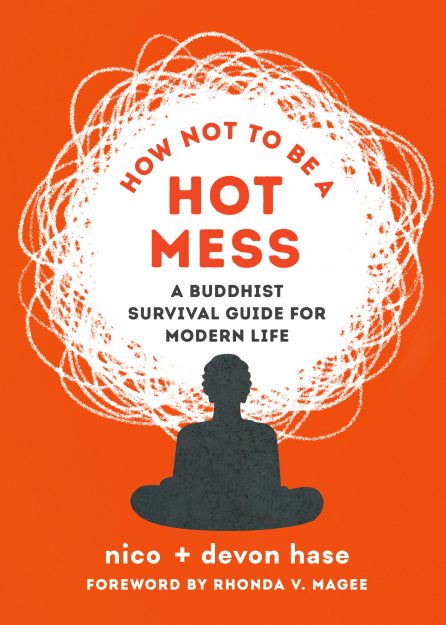

This article was originally published online in April 2020. Check out Devon and Nico Hase’s newly released paperback version of How Not to Be a Hot Mess: A Survival Guide for Modern Life here.

Adapted from How Not to Be a Hot Mess: A Survival Guide for Modern Life by Nico Hase and Devon Hase © 2020 by Nico Hase and Devon Hase. Reprinted in arrangement with Shambhala Publications, Inc. Boulder, CO.