YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

From humble beginnings to international textile art success, Dijanne Cevaal’s story is an illustration of the power of stitch, print and dye.

Living in an isolated part of Australia while raising her young family, Dijanne had little access to materials and tuition. Undeterred, she taught herself to dye, print and stitch her own fabrics.

She learnt to use natural vegetation from the Australian bush for her experiments on fabric and paper. Making sustainability and environmental concerns a priority, she developed skills that she could teach to others.

Dijanne has travelled, taught and exhibited in Europe, Australia and Asia, often working with small indigenous communities to upskill women.

She loves to tell stories about her travels and her interests in history, art, nature and the environment. Let’s take a look at how her richly textured cloth does that in the most tactile and visually pleasing way.

How do you develop your colourful and textural art?

Dyeing and printing fabric has been a part of my arts practice since the beginning. I had a limited budget when I started creating textile art, as I had a young family, and also because we lived in an isolated region. So I had to be inventive in creating my own fabrics. As time progressed, it became an important element in my work.

I’ve always been inspired by nature and environmental issues, as I’ve lived in a reasonably wild region of the world. I’ve seen the catastrophic effects of pine plantations, fires and farming, and how they’ve impacted all of nature.

My earlier work dealt with issues of bushfires – the Hellfire Series. That’s morphed into working with natural inks, again using sustainability and environmental concerns in this practice.

I’ve collaborated with Australian artist Cheryl Cook, under the name Inkpot Alchemists, to make natural inks with vegetation from the bush and from our gardens. I use them to colour and print on fabric and paper. Some of the vegetation for the inks has been sourced in very small amounts from the Crinigan Bushland Reserve, where I walk regularly.

The printing has developed into more elaborate linocuts over the years. I also print with nature itself, particularly when using natural inks. I like to think of it as a partnership with nature, which is full of surprises.

Today, my home is my studio, as I live alone in Morwell, Australia, a small city in the industrial Latrobe Valley in Gippsland, Victoria. When I collaborate with Cheryl, we work together in her studio in Tanjil South.

You’ve created a Stitch Club workshop – tell us about the artwork you developed during the process.

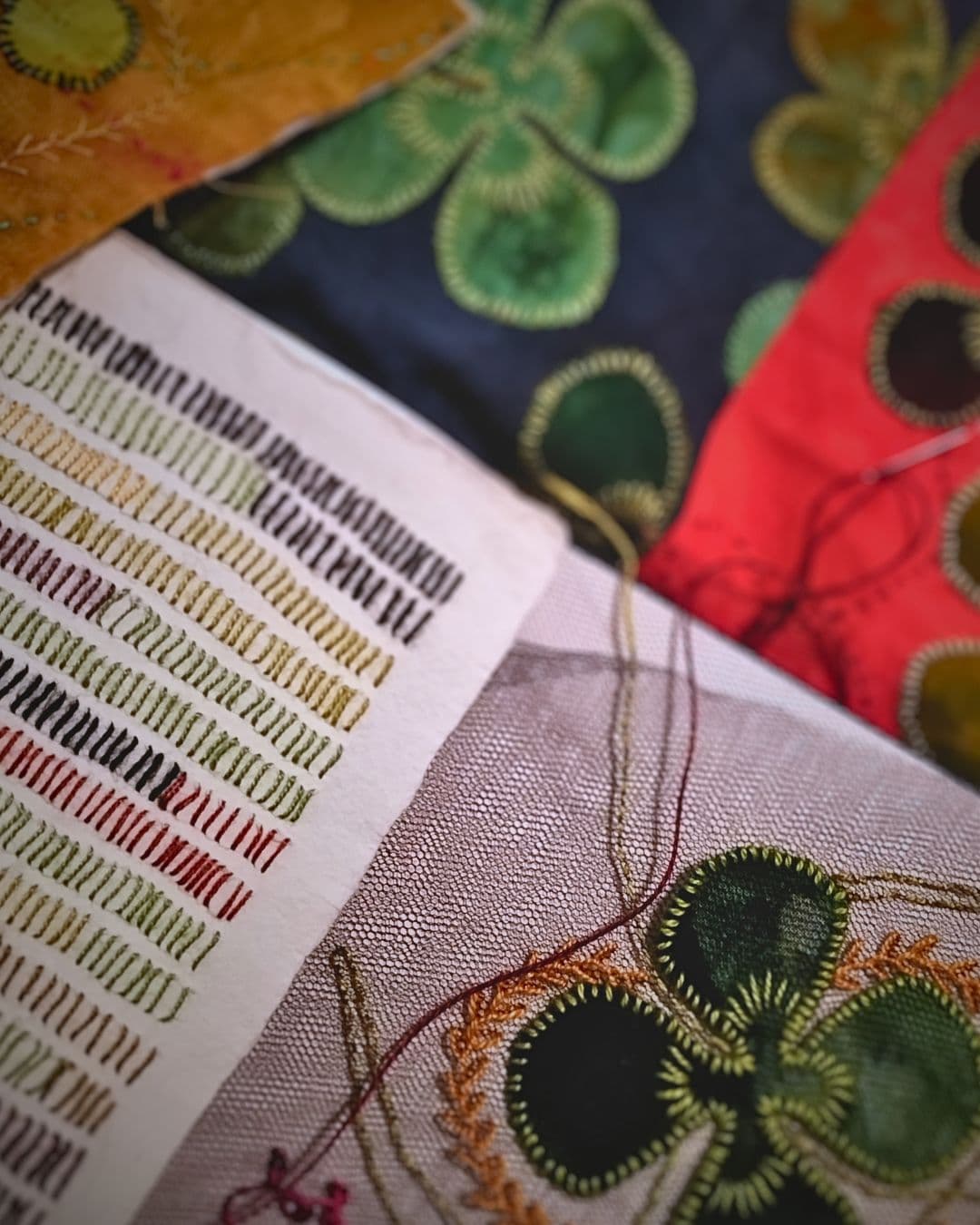

The artwork I created incorporates two of my favourite techniques: linocut printing and hand stitch, as well as a favourite subject matter, travel. The workshop is all about observations, play and stitch, and is inspired by travel, gardens and nature.

The motifs for the workshop were inspired by my travels in Perugia, Italy in 2023. I spent two weeks there visiting galleries and museums and enjoying the countryside. I was inspired by the ambience and history of this hilltop town in Umbria.

The work incorporates printing one’s own fabric inspired by travel encounters, and then stitching into it to recreate the rich textures.

I chose emblems I’ve encountered, which included rabbits on woven cloth in the artisan weaving workshop, Giuditta Brozzetti Museum and Atelier, and many representations of trees seen in paintings. I also include sculptures and posters, the griffin – the heraldic emblem for Perugia – and the many madonnas in paintings and textile designs.

The stitching enlivens and connects the images. This process is adapted from the type of work I do in my Traveller’s Blanket series, which are vehicles for telling stories of encounters and travels. The linocuts allow me to make printed fabric incorporating images from the place, and the stitching is the mark making that connects those images to create a whole.

How did you develop your artistic skills over time?

I was born in the Netherlands and my parents migrated to Australia when I was nine years old. When we first arrived we lived on a very large station (63,000 acres) 18 miles from Jerilderie, a country town in New South Wales. I attended the Australian National University where I studied Arts Law and practised for 10 years as a solicitor.

I was initially self taught in art and textiles, but in the early 2000’s I embarked on a master’s degree in visual and performing arts through distance learning. It saw me create work inspired by the history of migration in my own family, and interpret that using lace.

I could trace part of my family to the early 1600s and Huguenot French, which was a similar timeline to lace developing in Europe, and so I created lace reflecting this journey.

My work has always been about themes and series; in a sense, they’re stories and record my interests in history, art, nature and the environment.

When planning and researching, how do you develop ideas for your work?

I keep a journal, not a sketch book as such. I do draw in my journal and might keep interesting snippets of brochures or some such.

But a lot of my journal is writing – I might write about encounters, but often also the ambience of a place and the feelings it might inspire. The writing might be as prosaic as ‘I need to do more work’, but on the other hand might explore thematic or philosophical ideas.

This journalling process allows me to write about the work in an essay style, expressing ideas about, for example, the environment. It may or may not develop into a body of work or an exhibition, but it helps me to explore themes.

“My writing is a process of exploration and evolution – it can allow me to develop poetry around the theme, as well as visual imagery to use in my art.”

Dijanne Cevaal, Textile artist

I think about my work in writing, but not as individual pieces – more as a thematic body of work. I also go down many rabbit holes. I enjoy researching by way of books and or other media. I have quite a formidable, eclectic library.

I also mind map themes. If I’m really exploring a theme in depth, I’ll dedicate a separate journal for that. I’ll often start with a mind map to help me keep on track, but also to add things to, as I spend time exploring.

How do you begin a new artwork?

As I explore my theme by way of mind maps and my journal, I develop some ideas for printed images on fabric that help to tell the story. I then embellish those prints with stitch to create a rich, almost narrative, layer.

A lot of my work is intuitive, one thing leads to another, and I don’t necessarily plan or record those – it comes out of the process itself and I get carried away.

I’ll dye the fabric, as all my work commences with white or unbleached khadi fabric. I’ll then add print. I usually work with whole cloth and add stitch by machine and/or by hand. Sometimes I’ll add appliqué if the piece needs it.

In my artworks Coqueclicot I and II I used a technique called Tifaifai. If the designs are cut carefully, you end up with a positive cutout and a negative cutout, both of which can be made into finished pieces.

In my piece Medieval Concertina Book I’ve hand stitched mulberry paper, which softens beautifully as you stitch.

What fabrics, threads and other materials do you like to use in your work?

I use cotton fabrics, especially unbleached khadi cotton, obtained from The Stitching Project in India, which I hand dye.

I sometimes buy ordinary white cotton purchased from IKEA, or linen sheets bought secondhand at brocante markets in France. I source flannel for batting or other lightweight batting, textile printing inks, and cotton – usually cotton perlé #8 thread or linen (merlin) threads – from Fonty in France.

Where do you like to create your art?

I work in a dedicated workroom, though I tend to use most of my house for creating. My kitchen table is regularly used for the work I do with natural ink, and when the weather is fine I also work outside.

When I travel, I usually work on one of the travellers blankets, as this requires a relatively small kit: scissors, cotton perlé #8 threads and some needles, which means it can pack very small.

The blankets take so much time that it keeps me occupied the entire time I travel. But having said that, I usually am carrying an exhibition and my hand printed panels for sale, so there’s not much room for anything else.

My image of Journey Through My Surface Design is of works created in 2018 for an exhibition of travellers blankets. It was entitled Exploration Australia, Atauro Island, The Temptation of Persephone. All were entirely hand stitched and hand dyed khadi with a mix of applied linocut motifs or simply hand stitched.

Tell us about some of the art projects and residencies you’ve done.

My residency with Boneca de Atauro on the island of Atauro in South-East Asia was all about community, as well as teaching skills and ideas I had for the women to develop a marketable product.

Boneca de Atauro is a women’s group of 60-70 women: that varies depending upon need and capacity. It’s not fostered by an NGO but directed and driven by the women themselves. It’s been one of the most inspiring and communal ways of working I’ve seen.

As such, it wasn’t really about developing my own work, though it inevitably did.

It was more about helping to improve the women’s skills. As a teacher in an environment where scholastic learning was absent, except amongst the younger women (and then usually only basic level education because they were girls), it took a little while to settle in. Also, they spoke very little English and I spoke no Tetun and only small snips of Portuguese.

I couldn’t just march in and lay out the skills; I had to observe how they worked and how they learnt.

They worked a lot with treadle machines. I’d never actually worked on one so I thought I should learn. In a way, it was this that broke the ice.

I wasn’t instantly good at using a treadle machine, and so nearly every woman there showed me how, or would gently guide me.

“This learning interchange resulted in equalising our relationship, so the women became receptive to learning from an outsider.”

Dijanne Cevaal, Textile artist

Culturally, their hierarchies are circular, not linear like Western societies. They needed to make a presentation to the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs for a working grant. So we sat and mind mapped so that I could comprehend, but also present, their case for them in a more understanding way. It was an amazing experience and I do hope to go back.

It’s very difficult for the group to source supplies, and the fabric they work with isn’t good quality cotton. The small island is 20 nautical miles from Dili, the capital of East Timor, so there are many logistical difficulties, which makes their story all the more inspiring.

I’ve also worked with The Stitching Project in India, working on stitching and teaching skills to some of the women. As they use a lot of woodblock print, I showed them ways to incorporate stitch into the patterns created by the woodblock.

My one big takeaway has been to be inspired by other ways of working, and to look, watch, understand and learn.

In the year 2000, I co-curated, with Frederique Tison, a travelling exhibition of Australian Art Quilts. They were shown at Chateau de Chassy in the Morvan region in France.

Coincidentally, 2000 also happened to be the year that the Olympics were held in Sydney, Australia. We were the only Australian Textile and Art exhibition in Europe, so it attracted much attention in France and ended up being shown at the Australian Embassy in Paris.

This led to curating more Australian Art quilt exhibitions, one of which travelled to the Middle East at the invitation of Robert Bowker, the Australian Ambassador to Egypt, Syria and Libya. I accompanied the exhibition for much of this, demonstrating and installing it.

These exhibitions included 30 works by Australian quilt artists and were much appreciated for their innovation, colour and expression of place.

Which piece of your textile art is your favourite?

I don’t have a particular favourite, but I do enjoy working on the travellers blankets, as these are entirely stitched by hand and are storybooks of a sort.

I also enjoy working on my sewing machine, usually on whole cloth heavily stitched pieces. My favourites amongst machine work are the forest scenes, as these allow me to make comments about the environment and nature, and to interpret nature.

What do you think are the biggest challenges you face as a textile artist?

Breaking down the prejudices of textile being art and the perceptions that it’s a little hobby that women do. This lowliness in esteem means that textile artists often have to teach their techniques in order to sustain themselves, which means taking away energy from art creation.

Galleries have been very slow in accepting textiles as art. It’s the double whammy of being perceived as having been ‘made’ by women and actually being ‘created’ by women. And we all know that women are underrepresented in the gallery system.

“Technique alone does not produce art – it’s the ideas, interpretations and visions that make the art.”

Dijanne Cevaal, Textile artist

What advice would you give to an aspiring textile artist?

Mind maps really help – it helps to focus ideas and establish avenues of research and exploration.

And keep doing the work: working consistently and daily helps establish a pattern of work, but also allows daily time for exploration. Working sporadically means you start over each time, but working daily, even if it’s only for an hour, helps establish continuity.

The techniques I use and the materials – dyeing and printing my own fabrics – allow me to tell stories of places visited and encounters with nature. These kinds of techniques allow for very individual expression and help me to develop my own voice.

“My needle and thread are my pencil and mark making tool – the fact that the stitching produces texture is an added bonus.”

Dijanne Cevaal, Textile artist