YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

Born in Kathmandu, Nepal, to Tibetan refugees, Tenzing Rigdol attended the University of Colorado Denver School of Arts & Media and was awarded a BFA in Painting and Drawing and a BA in Art History. Since graduating, Rigdol has built a career as a contemporary visual artist working across a range of mediums, including sculpture, painting, collage, performance art, and more. His pieces, infused with sociopolitical undercurrents, often address the pressing issues of today through Himalayan Buddhist imagery. Said pieces have been exhibited internationally at the Rubin Museum of Himalayan Art, Asia Society, Tibet House Gallery, Rossi & Rossi Gallery, Nobel Museum, and Glenbarra Art Museum, to name a few. Biography of a Thought, Rigdol’s most recent installation, is the centerpiece of the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s current exhibit “Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet,” on view through January 12.

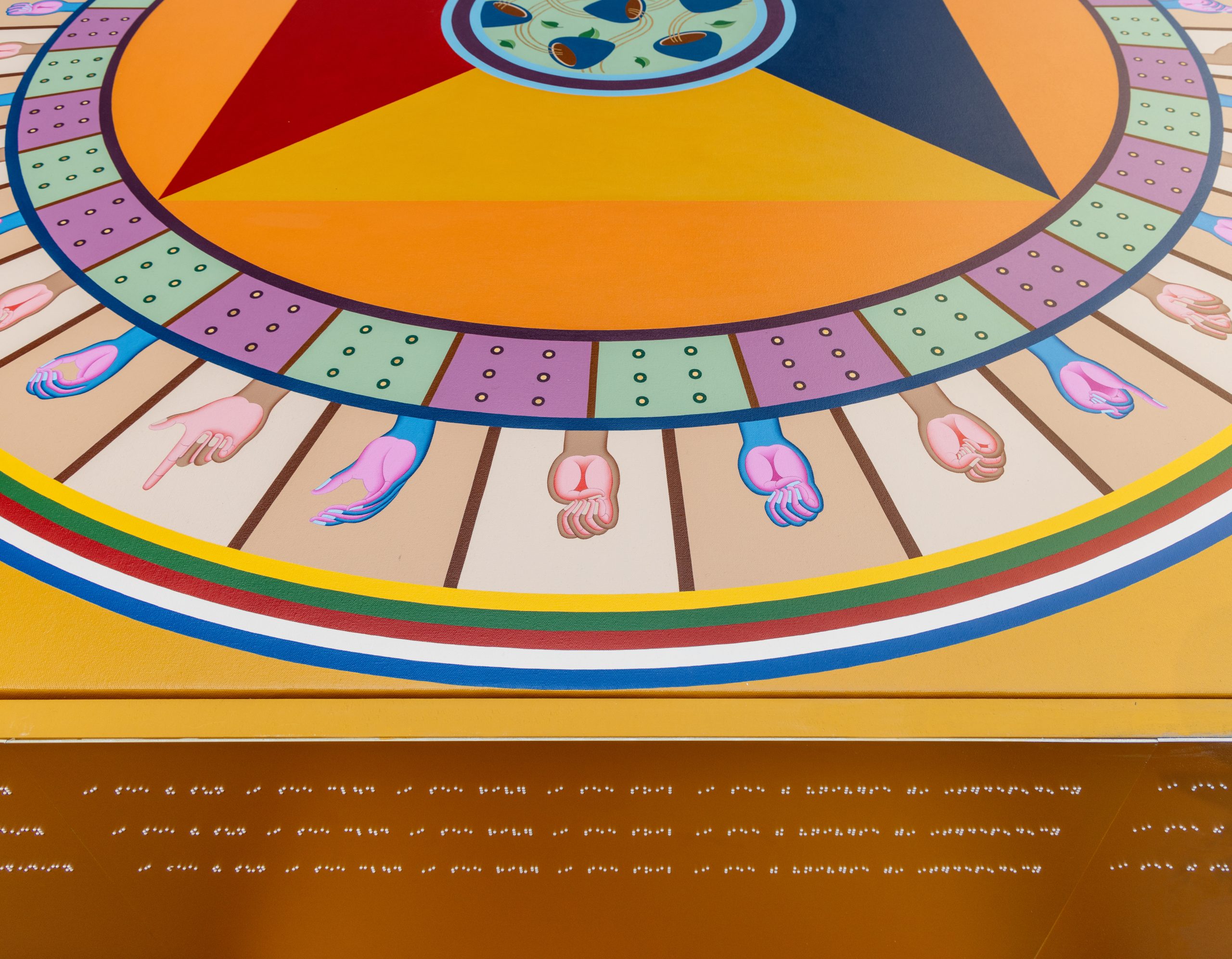

Situated in the Robert Lehman Wing, “Mandalas” allows visitors to explore Tibetan devotional art from the 12th to 15th centuries through a series of corridors lined with paintings, sculptures, textiles, instruments, and an array of ritual objects. These early masterworks are juxtaposed with Rigdol’s expansive modern installation in the collection’s sunlit central gallery. Over five years in the making, Biography of a Thought features four thirty-foot-long paintings, a pillar with braille and American Sign Language, as well as handwoven carpets.

Tricycle’s Haley Barker recently talked with Rigdol about his oceanic inspirations, the demands of scale, and the universality of different spiritual traditions. For more on “Mandalas: Mapping the Buddhist Art of Tibet,” read Dominique Townsend’s recent exhibition review, “Mandalas at the Met.”

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Biography of A Thought is huge, and filled with Buddhist iconography and sociopolitical imagery. How did you approach this commission conceptually? Basically, Kurt [Behrendt] showed me the space [the Robert Lehman Wing]. He wanted to do a big “Mandala” show. This was before the pandemic. When I saw the space, I thought, “Yeah, I have some ideas.” So [the whole process] started over five years ago; it took me about two and a half years to do the study of the composition, then about three years to paint it and to produce the carpet.

At that time, I lived in Astoria, so there’s the Atlantic Ocean. For months, I would always go there and look at the ocean. I would look at small parts of the ocean, and then try to study how it breathes. Then the main composition was going to be waves and the clouds. Clouds are like the thoughts, and waves are like the emotions. You weave the two stories and ideas together, and that was the idea.

OK, so you took inspiration from the ocean. I see it, because your piece is very blue, and the clouds are rich and colorful. Like the thoughts! You know, our thoughts are sometimes vibrant, sometimes dull—sometimes thoughts are all gathering [together], almost like [they are] talking to each other. I thought it would be interesting to represent thoughts as clouds, and there are many Buddhist references there too. I played with that iconography.

Are there specific details of the composition that stick out to you, or that are your favorites? Not really, because interestingly, there are three ways to install it. One way to install it is to put all the paintings together into one painting, and it’s 120 feet long. Another way of composing it is having a central piece, and all the surrounding pieces become a circle. And then the third way of presenting it is where it’s opened up on four walls, like you’re entering my mind—basically like the Buddhist idea of tantra. In Buddhism, too, you have three ways of experiencing the teachings: through Theravada, Mahayana, or Vajrayana. I play with that. And since it’s one complete composition, the idea is to really pay attention to every corner of each percentage of the painting. So there’s no picking [a favorite]. If something works, it’s because other things are supporting it. We look at the totality of it.

I see! Going off that, can you speak a bit about how the size of this work changed or challenged your creation process? In a way, it did. Initially, we were thinking of starting with one painting, then two paintings, maybe four paintings. Then the size really was dictated by how strong the light was coming into the space. The walls are very intimidating, in a way. They are very big walls. If I had small pieces, like four small paintings, it wouldn’t work. So it grew in that way. Within a few months, we realized it had to be big in order to fit the space. Many things were dictated by the space. And the idea needed a fixed space so that I could explore it properly, with what you call “complete satisfaction.”

I read in your interview with Behrendt that you had to get a whole new studio space to work on this, because it had to be big enough to accommodate the size of everything. I wanted to have a studio that had almost the same light. That’s sunlight, so I built a studio in Nepal on the fifth floor, and I had all the surrounding walls be only windows. I had all the sunlight coming in. In that way, I built a whole studio that fits the thirty-foot paintings.

And you were working in that studio, specifically, for three years? Yeah, three years—my retreat. I call it an art retreat. I think tantra is all about one’s ability to pay attention, and what attention means, and how one can harness it. That kind of subject matter would naturally demand a quiet place to explore and execute. It’s almost like you’re painting while there’s an egg on your head. You really slowly calm yourself.

What did you learn about yourself through making this piece? I learned how to slow down. That was very difficult. And to release effort. But I think it’s not that you’re learning but you’re actually discovering. Maybe you’re learning how to be calm, but that leads you to discover things about yourself that are already there. I think what I learned or discovered is that it’s amazing to just paint and spend time on something that big.

There are so many details to the composition, so many little Easter eggs in every single corner. Can you take us through some of it? You can enter the room from any space. After a while, you start seeing simple repetition. Then you notice somewhere that the waves are fluctuating, the clouds are more vibrant. Slowly the clouds and waves settle. So the initial experience is immersive. It’s something that somebody who doesn’t really know anything about Buddhism can experience—energy.

The first panel talks about natural phenomena. It talks about the environment on a surface level; air pollution, water pollution, deforestation. But at the same time, at a deeper level, it talks about our awareness, being thrown into this world, being here. And all the symbols are very hidden, like how tantric texts are. The second panel talks about what happens when the mind gets wild. Suffering—not who created it or how it is in this country or anything like that—but just suffering and how people respond to it. In one of the paintings [on this panel], I used this old picture of His Holiness the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. He was giving an exam and debating right in front of Potala. I removed the monk he was debating, and I put a Chinese hat there. It is talking about how many people are so violent right now, but there are also some people who believe in dialogue and nonviolence as a solution. So this second panel really is about vritti. We call it modulation. Vibration.

All my artworks are like a stage for the mind to dance.

And on the third panel, you start seeing how to stabilize the mind, how to look at identity. I used Picasso’s five women [Les Demoiselles d’Avignon]. People say, “Oh, they’re from the brothel,” and this and that. So I re-created it and added the five primordial Buddha’s colors. And I added the five mental faculties that he was offering. When you properly tune the five mental faculties, you see they’re all buddhas. In a way, I’m saying your soul doesn’t have a gender; [the same is true of] your atman or rigpa or whatever you call it. You’re much more than your thoughts and body. That was one of the tantric teachings. And then the fourth panel is calmness.

My friend is an Indian scholar. He wanted to know about the painting. In a very simple way, I explained it like this: In the Patanjali Yoga Sutra, the second yoga, Chitta, is the first panel. Vritta is the second, nirodha is the third, and the fourth is the yoga. [laughs] You can look at it in so many ways, but I’m just giving you the general melody. If you go into detail, it’s crazy. I remember once I went with Kurt and Mike [Hearn], I think we talked about it for three and a half hours.

How do you see people engaging with the piece? I think most of the people that come have no memory of Buddha, so it’s very interesting. They respond to just the melody of it. It’s almost like you go to a country where you don’t speak any language and you don’t know the content of it, but you know the melody. And sometimes, many people come, especially elders and kids, and they don’t ask much. They just walk around, and they hug, and some elders cry and they just say, ‘thank you.’ I don’t know what they understood. I don’t know what I told them. Sometimes I say all my artworks are like a stage for the mind to dance. I create a stage, and I create that stage as smooth and as effortlessly as possible. And hopefully each individual brings their own mind, and then they dance around, and then they explore the plot. And in the end, what they’re exploring is themselves. So whatever one sees, it is seen through their own history, experiences, and interests.

I’ve read that you consider much of your work to be secular, even though a lot of your work uses some pretty overt Buddhist motifs. So how does Buddhism inform your work, or the creation of it, and how do you square that with your intention to be more inclusive? I have always visited places or institutions to really learn something. You don’t go there to feel like you belong. Let’s say you’re a thangka painter, and if you think about yourself as a thangka painter, then you’ll start seeing everything like a thangka. That’s not freedom, because you’re looking at it from a specific angle. Sometimes, even being a Buddhist, I also might not have the most perfect vantage point, because you can think, ‘I am a Buddhist, they are non-Buddhist.’ You can go even more fundamental. To whom did Buddha prostrate? I think his teaching was for us to become like him. And he bowed down to basic principles. In that way, Buddhism helped me look at all the other religions together.

I see. Buddhism is the vessel that allows you to see things differently and make different connections. Yes. You know, it’s like if the 7 train goes out to Jackson Heights, Queens, it also goes back to Manhattan too. So it’s not ‘Buddhism is very special.’ It’s just that all religions are like different subway stations. When you combine all the stations, it’s like one circle—like prayer beads!

I was brought up with Tibetan culture, and I naturally have more information about it. But, of course, I see suffering in Kashmir. I see suffering in Hong Kong. I see suffering in different places, and I see Mount Tibet in those places. I’m talking about a kind of universality. It’s happening everywhere. Tibet is everywhere. The injustice, suffering, discomfort, disease is everywhere. And every country has its own homework to do. I think it’s time to look within oneself, one’s own country.