YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

At first glance, a collection of subdued, black and white photos of and by Allen Ginsberg might not make immediate sense next to colorful, pop-culture-packed collages from Tibetan-born British artist Gonkar Gyatso. Even viewers who are aware of the two artists’ Buddhist backgrounds may need a moment for the juxtaposition to fall into place. Luckily, the art on display from the Ginsberg estate and Gonkar at Beats and Buddhas, an exhibit at the Dash Gallery in Kingston, New York, invites viewers to spend time contemplating and connecting the dots. Political, spiritual, and attuned to the details of everyday life, the artists—and their work—compliment each other perfectly, in fact, and it becomes only more fun to appreciate them in tandem the longer one explores the three-room show, up until August 19.

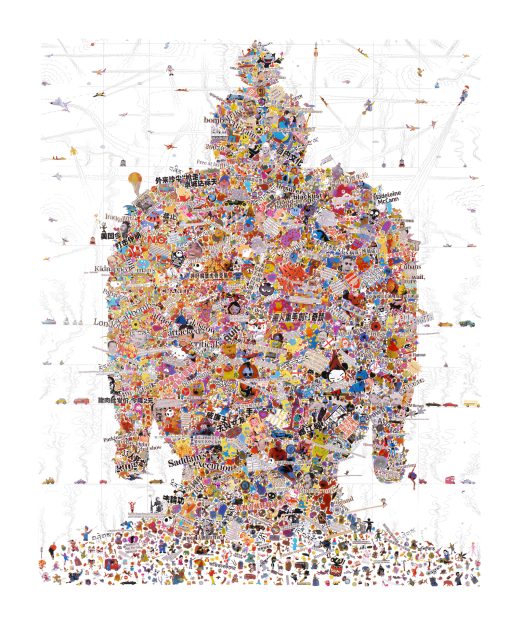

Beat generation activist, writer, and poet Ginsberg, who became a practitioner of Tibetan Buddhism later in life, was prolific at documenting his generation, capturing photos of daily interactions and specifically his friends. Gonkar, who was born in Lhasa, Tibet, in 1961 and currently lives in China and the UK, is known for combining Buddhist iconography with pop-culture references in the form of stickers or cutouts from magazines and newspapers. His work appeared at the 53rd Venice Biennale (2009) and the 6th Asia Pacific Triennial (2009-2010), and can also be seen at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in Israel, and the Chinese National Art Gallery in Beijing.

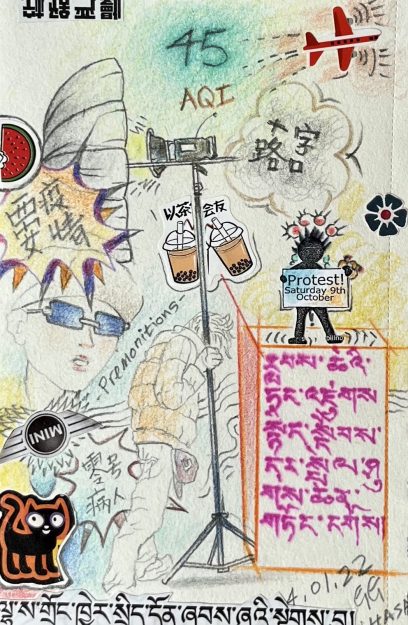

Beats and Buddhas opens with a rare collection of Ginsberg’s doodles, which sets the mood for the playful—but also serious—scenes that follow, whether it’s well-known photos of Jack Kerouac and Patti Smith, or a Buddha head composed of tiny stickers and provocative words. Though only scribbles and fine lines, the doodles are deeply expressive, also a harbinger of the show that is—quite literally—around the corner.

In his black and white photos that line the walls of the next two rooms, Ginsberg draws viewers into his world with intimate scenes that are often mundane (even if they feature his famous friends) but also often humorous. In one photo, Ginsberg had writer William S. Burroughs pose next to a sphinx at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City because he thought the two looked alike.

In another, writer Jack Kerouac looks into a storefront or barroom doorway across from Tompkins Square Park in what is at first an everyday scene without much animation, but then becomes a scene of fascination as it implores the viewer to consider the object of Kerouac’s gaze.

Other photos from the collection include Ginsberg on his apartment roof in New York’s East Village, Burroughs and Kerouac on a couch in Ginsberg’s apartment, and a highly focused Harry Smith pouring milk into a glass jar—a tongue-and-cheek depiction of the “anthropologist, entho-musicologist, bibliophile, innovative animator & film-maker, painter, designer, metaphysician & hermetic alchemist,” as Ginsberg writes in the photo’s caption. Above all, the reverence Ginsberg has for his friends and his community come through, the relationships seeming to trump whatever malaise or frustration lies in the cultural subtext.

Although Gonkar’s work feels less intimate, it is no less powerful. The images are arresting and mesmerizing and arouse a sense of disease and serenity at the same time. Like with Ginsberg’s photos, humor and irony are also immediately evident in Gonkar’s work, whether it’s the geometric designs made from Buddha stickers—some upside down—and collages posing symbols of consumerism, like bubble tea and a jet, next to cartoon characters and political images.

Darker undertones emerge upon close inspection, however. In one untitled geometric pattern, meditating monks have their faces scratched out. In another collage, a man in a coat and tie sticks his head in the sand. One of the centerpieces of Gonkar’s work in this exhibit is a sculpture of a meditating monk, in lotus position. The sculpture has no head, however, and is positioned in the middle of a wall so that viewers see the apparently floating meditator from behind, with his missing head appearing to be stuck in the wall. Is he also burying his head in the sand? Or has he been released from samsara? A frame of colorful stickers around the floating sculpture drives home the sense of irony.

The other central piece is a Buddha head—a classically serene image—almost brutally packed with a storm of endearing pop-culture stickers alongside words with violent associations: “bomb strike,” “London car bomb,” and “Saddam’s execution.”

Gonkar’s use of words to bring further dimension to his visual art reflects that of Ginsberg’s hand-written captions, which accompany most of his photos. Hard to read but full of personal context for the images at hand, Ginsberg’s captions—like Gonkar’s collaged words—aren’t ancillary, but rather urge viewers to look at the artwork with another part of their brain, focusing via a different lens. Wordsmiths and visual artists, beats and Buddhas. The artists buoy their unassuming cynical tenor, only apparent upon close inspection, with friendship, faith, and humor.