YOUR CART

- No products in the cart.

Subtotal:

$0.00

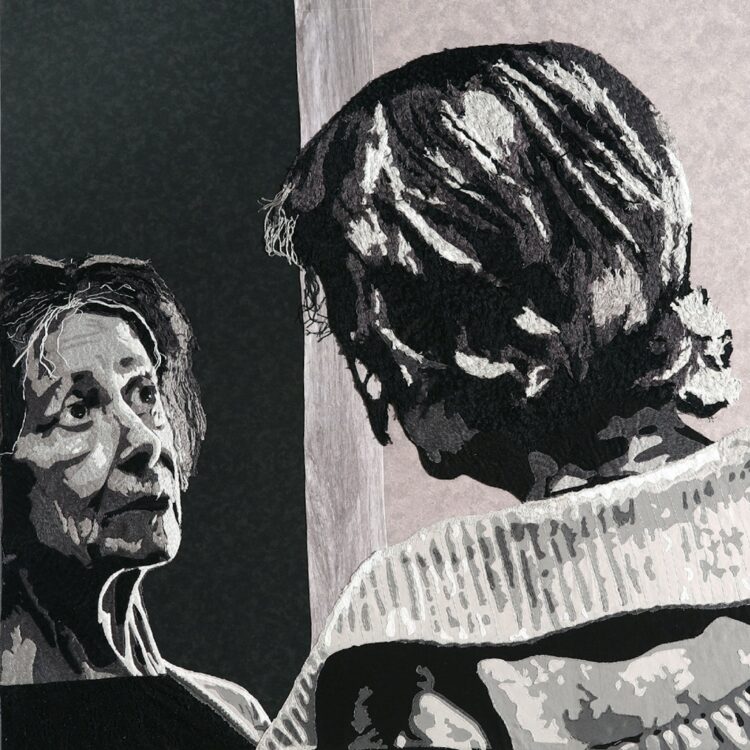

Aran Illingworth has stories to tell, and many can be hard to hear. Having worked in nursing and social care, Aran saw firsthand the impacts of homelessness, poverty and social deprivation. Her textile portraits now bear witness to those experiences, walking the delicate line between pain and hope.

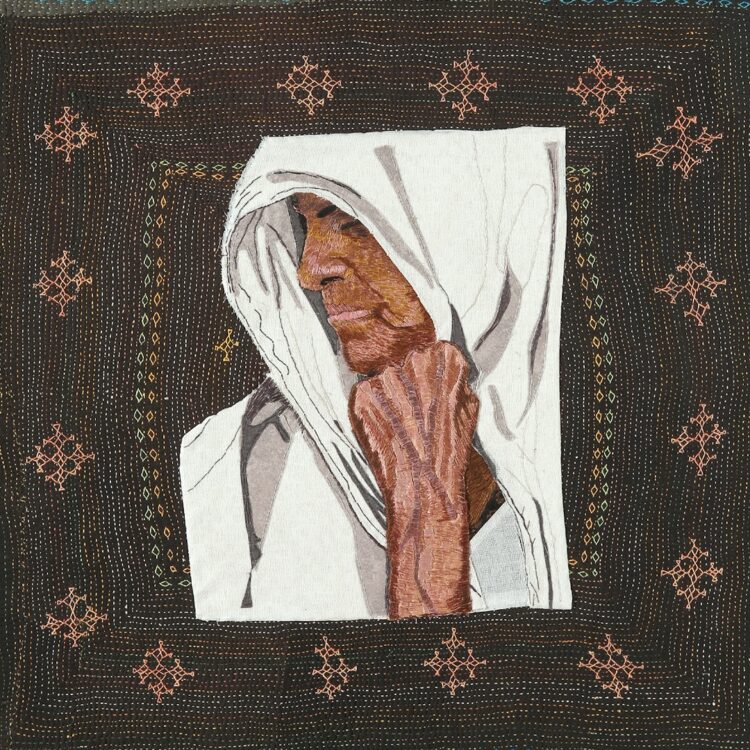

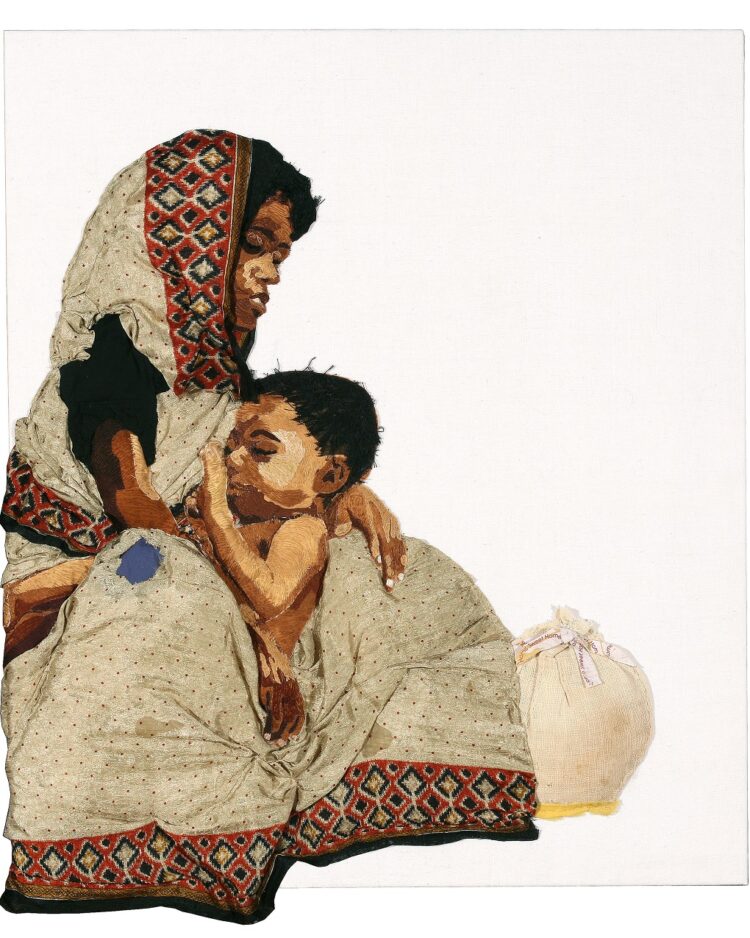

Aran’s Indian aesthetic is clearly present through her use of intricate appliqué and stitch. Bold colours are layered to create images of traditional garments and settings. Viewers can easily imagine the bustle of busy streets or the spices in the air that surrounds her portraits’ figures.

Still, not all of Aran’s stories are so bittersweet. The pandemic lockdowns inspired her to explore ways to stitch the birds and other wildlife she saw on her daily walks. Of course, she still infused traditional Indian imagery in those works, including an artistic nod to a particular Indian artist from the late 1700s.

Aran’s portfolio is an important reminder that art is not only about beauty. It also has huge potential, and dare we say an obligation, to tell stories that make us uncomfortable at times. Welcome to Aran’s world.

My earliest memory of working with textiles was using my mum’s sewing machine. I was eight years old, and I particularly remember getting the sewing needle caught in my fingernails! Thankfully, that experience didn’t put me off sewing, and I continued under my mum’s guidance. My mum had enormous skill and experience in working with textiles. She also taught me how to crochet and embroider.

Although I was initially self-taught, upon leaving nursing and after the birth of my son, I decided to get formal training to help develop my skills. I first completed A-levels in a variety of art courses, along with various City and Guilds courses and diplomas. In due course, this led to completing a BA Degree in Applied Arts at the University of Hertfordshire.

I love textiles, especially the colours they provide and their versatility as an art medium. And from the start, I’ve sought to produce works that use textiles in ways that replicate a fine art piece.

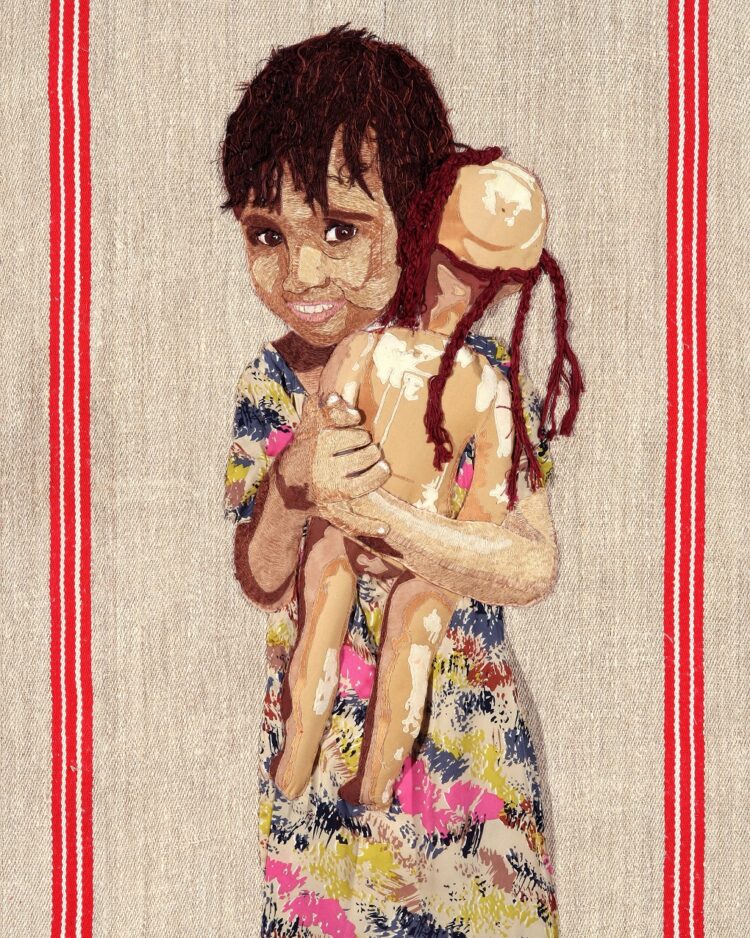

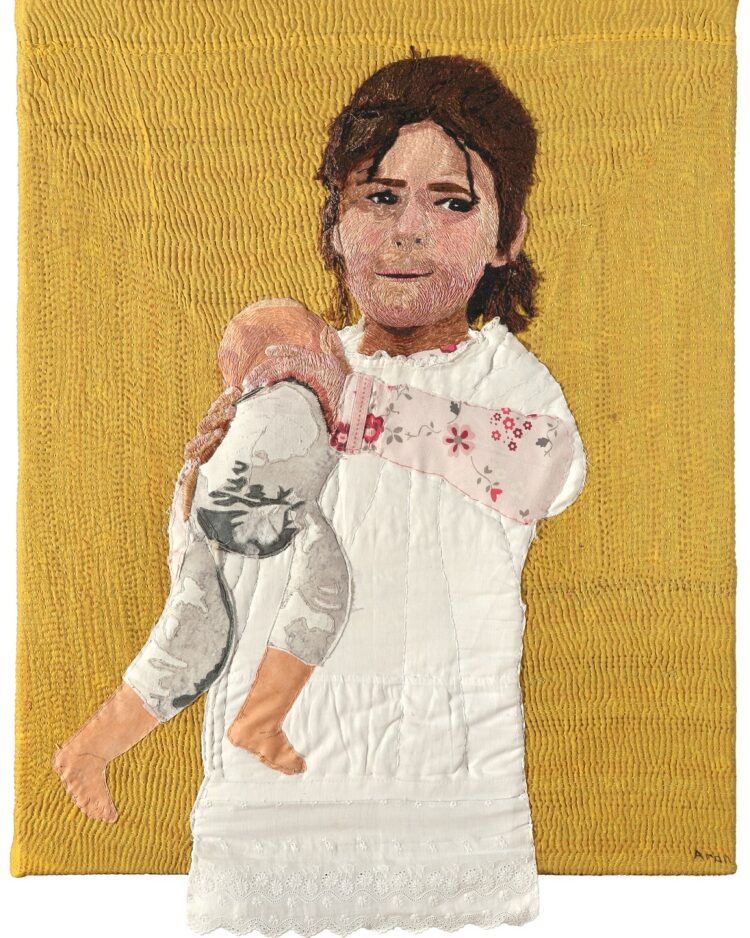

My sense of form and colour is informed by a specifically Indian aesthetic. This is especially apparent with my use of vibrant colours in my works featuring Indian subjects. For example, When We Were Very Young features a vibrant use of colour in its depiction of a young Indian girl holding a badly broken, but cherished, doll. I made two versions of this work and, although the mood varied between the two pieces, the vibrant sense of colour did not.

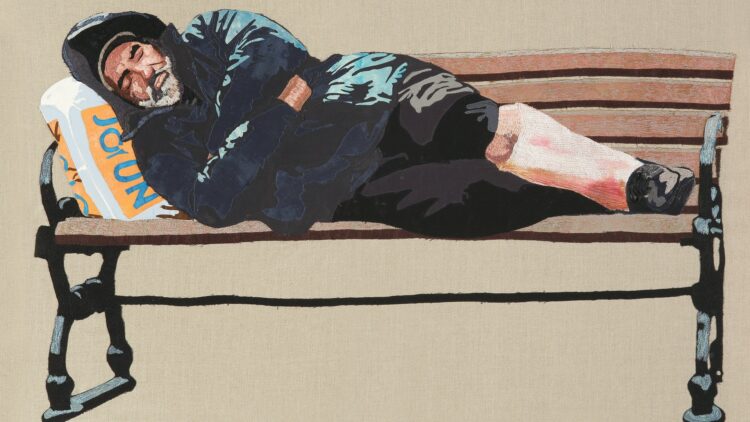

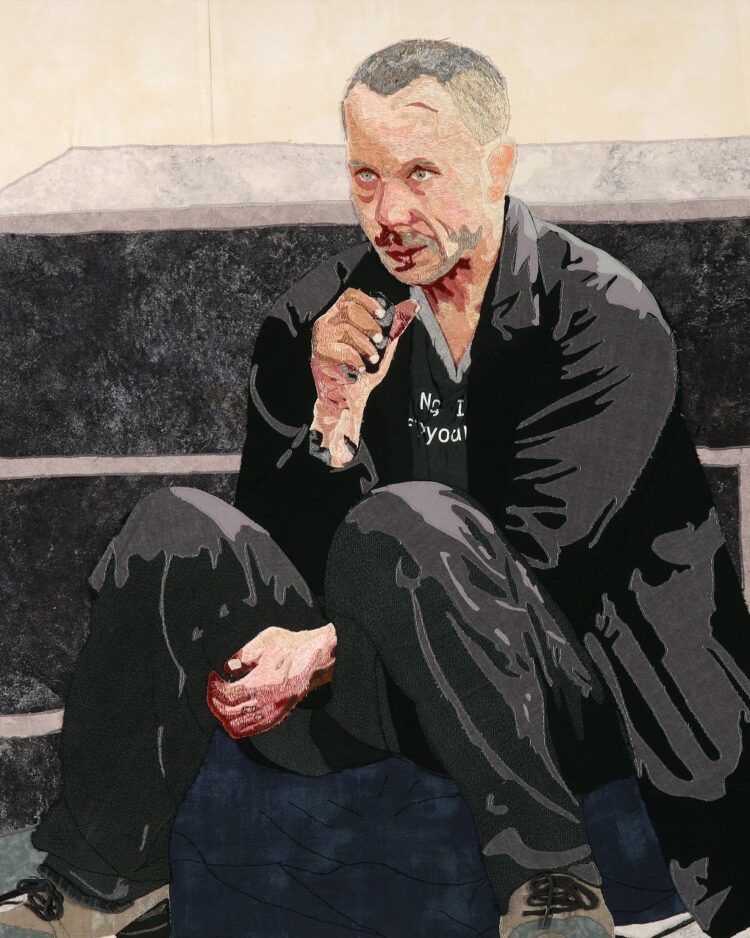

However, if you look at my more recent work, such as The Man and His Friend II, the colour of the homeless man’s clothing is particularly striking. But those colours weren’t present in the original photograph I used. I introduced the colours myself as an expression of my Indian colour sense.

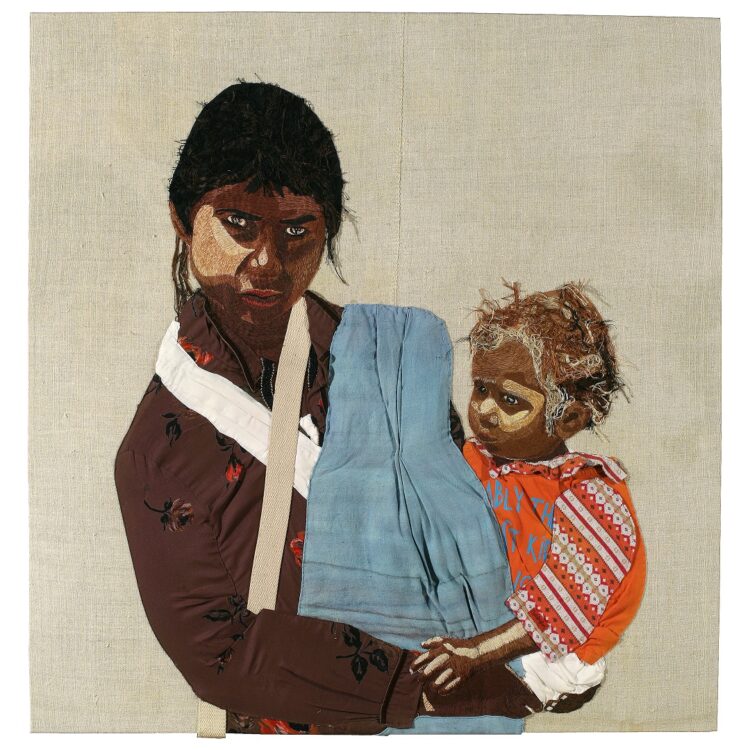

In terms of form, Madonna and Child, which depicts a young mother living on the streets of Delhi with her child, captures the sense of movement in Indian sculpture, such as Chola statues from the 12th century and even earlier works. To that end, my work at one level can be viewed as a current manifestation of a much older tradition.

I aim to produce images which evoke a clear emotional response in the viewer that can range from compassion toward the poor and a heightened awareness of their predicament to lighter emotions in relation to less politically charged subjects.

My concerns around poverty and social deprivation strongly reflect my background in nursing and social care. I originally trained as a psychiatric nurse where I saw the results of poverty and deprivation on a daily basis: homelessness, alcoholism, drug dependency, and psychiatric disorders in offenders as well as other types of people.

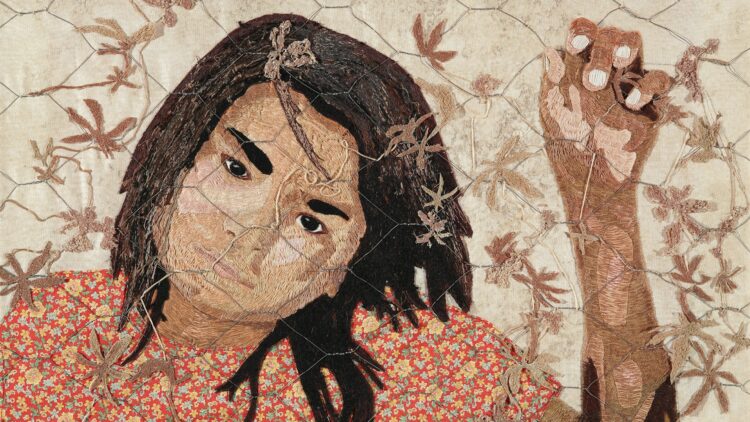

For example, Rabbit Proof Fence expresses how children’s voices can go unheard in society, especially those that are destitute and displaced. Those children struggle for life every day, and they are victims of forces beyond their comprehension, as their fundamental rights are disregarded and trashed. On The Bench features many shades of hidden meaning about the juxtaposition of the untold wealth of experience and untold suffering experienced by the homeless and refugees.

My concern with dementia and other age related issues also arose naturally as a continuation of my work as a nurse. Remember Me addresses the way dementia undermines and finally destroys the powerful memories and emotions that hold the secret of happiness and sadness in the life of the sufferer. Thankfully, life changing research with the aim of eliminating dementia continues.

During lockdown, I started featuring animals and birds in my work, as I spent a lot of time in the garden and taking short walks watching for birds. I love wildlife, and I see quite a variety where I live in the countryside by a lake. I decided to challenge myself to create birds for a change.

Heron was inspired by a heron I’d always see on my walks. I sought to incorporate an Oriental artistic style. Black Hooded Oriole was my take on Shaikh Zain Ud-Din’s artwork using opaque colour and ink on paper from the Impey Album, Calcutta, 1778.

Both The Man and His Friend and The Man and His Friend II combine themes of social deprivation and animals. In human relationships, love is not always unconditional and can become warped through ulterior motives or other pressures. But animal love is unconditional, and for the homeless their animal might be their only relationship. Their pet provides a source of courage, strength and love free from any warping effects among humans.

Ideas for my work are ultimately generated out of the passion I have for certain themes. They can be socially relevant, such as homelessness, forced migration and dementia. But themes can also reflect other concerns and interests, such as wild animals, flowers or landscapes.

When looking for a subject for a new work, I generally start sourcing photographs and other images. I often use the Internet, although I’ve also used photographs taken by me or my family and friends. I look for images that resonate with me and speak to my concerns and sympathies. It’s essential that an image evokes a sufficient response in me.

Once I choose an image, I use my computer to electronically posterise and resize it to my preferred dimensions. But from then on, the focus shifts to the subject, the person in the portrait. The background follows at the end once the main image has been completed.

There are several stages in creating the subject’s image. I first print the posterised image and then trace the different sizes and shapes to create a template for building up a layered image. I then trace the individual template shapes onto fusible webbing, which will be ironed onto corresponding fabrics. Using a good pair of embroidery scissors, I cut out each fabric piece, taking care to leave extra fabric along any edges that will be tucked under adjoining pieces.

After cutting all the pieces, I start the jointing process by assembling them on a separate piece of calico. As I go along, I check the accuracy of the assembly by placing the traced template on the fabric. I refer to the original photographic print from time to time for visual reference. I also take care to ensure the backing paper of the fusible web is peeled off before assembling the pieces.

Once I’m pleased with the assemblage, I iron everything onto the calico. And then I start the process of hand stitching to add details to the eyes, teeth and other prominent features. The stitching really brings the pieces to life, but nothing would be possible without putting the appliqué framework in place first.

When stitching over underlying appliquéd fabrics, I follow an unwritten method, which I have developed over several years to achieve my desired effect. A methodical approach is essential, as impulsive stitching wouldn’t give the quality of work to which I aspire. I mainly use backstitch with a single floss of cotton thread. As time has passed, however, I have sought greater intricacy in my stitching, so my stitching is ever more like painting with thread.

I have also introduced machine stitching for some parts of my images, as well as fabric paint. On the Bench is a good example in which the bench structure is machine stitched, and the homeless man’s leg is partly painted with fabric paint.

Work on the background only happens once the main image has been completed, and the time it takes to complete a background varies widely among different works. In some instances, the background is a plain fabric mount without detail, such as with Madonna and Child, Madonna and Child III and On the Beach. However, the background can be much more elaborate, as in East of Eden.

I can’t say textiles are better or worse than any other media for expressing my concerns. However, because textile art has historically been undervalued and overlooked as an artistic medium, part of my challenge is to correct that false impression.

Textile artists are constantly confronted with the artificial distinction between fine art and textile art. Textile art is widely regarded in artistic circles as a lesser art form. Terms like ‘applied’ or ‘decorative’ art are often applied, as well as ‘craft’. This appears to be at least partly due to the association of textile related activities with domesticity and femininity. The fact textile art can also serve a practical purpose also poses a challenge in the fine art world.

These attitudes have always been a challenge for me, but I’ve never turned back or been tempted to look at any other medium. I have always been fascinated with both textiles and creating realistic images, and I continue to fight to be seen and heard.

Aran states on her website that she wants her work to serve as an indictment of India’s social condition in the 21st century. Her passion to confront poverty and social injustice informs virtually all of her work. In this regard, consider the following:

Aran Illingworth is Malaysian-Indian by birth. Currently based in Cottenham near Cambridge, she has lived and worked in the UK since the 70s. Aran earned a BA Degree in Applied Arts from the University of Hertfordshire, and her work is exhibited in the UK and internationally.

Artist website: www.aran-i.com

Facebook: facebook.com/aran.illingworth

Instagram: instagram.com/aranillingworth

Interested in other textile artists who use their art to address important social issues? Check out Nneka Jones’ work, which tackles important social justice issues in the United States.